How should society manage its common-pool resources like fisheries, forests, and grasslands?

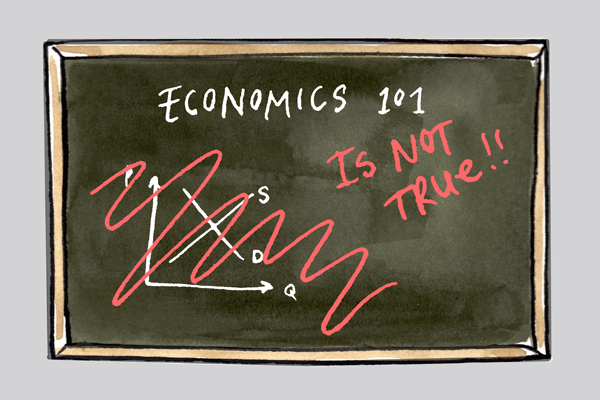

The problem, as presented in an Econ 101 course, is that these systems lack the proper incentives for sustainable use. Without private property or government regulation, people inevitably overuse and exploit them. This is the “tragedy of the commons” —famously formulated in a seminal 1968 paper by ecologist Garrett Hardin, and taught to thousands of economics undergraduates every year. There’s just one problem: Tragedy of the commons fails to explain real-world behavior.

Hardin’s argument runs something like this. First, he invites us to “picture a pasture open to all.” In this scenario, herdsmen of the pasture, if they are rational, self-interested agents, will figure that the benefits they receive from adding one additional cattle to the pasture outweigh the costs from overgrazing that are shared by all the other users. Each herdsman continues to add cattle to the pasture, but in this way, the resource is inevitably depleted.

For this reason, Hardin argued that “Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush.”

Scholars—many outside the economics discipline—have attacked this argument for its unrealistic assumptions and lack of evidence. One prominent critic is Elinor Ostrom. Elinor Ostrom is a lifelong researcher of the commons and Nobel Laureate in economics. Ostrom said that Hardin confused a joint property commons with an “open-access regime,” where restrictions on use are completely absent. Open-access regimes sometimes do exist (e.g., fishing on the high seas). However, in the real world, common-pool resources are often governed by rules and norms that their users develop. This means Hardin’s “pasture open to all” does not accurately map how the commons operate in practice.

There is ample empirical evidence for the sustainability of commons regimes—as defined by Ostrom.

The very existence of the commons, particularly where resources are scarce, proves neither private property nor state coercion is a prerequisite for their viability. In the words of Ostrom and her colleagues: “although tragedies have undoubtedly occurred, it is also obvious that for thousands of years people have self-organized to manage common-pool resources, and users often do devise long-term, sustainable institutions for governing these resources.” Commons are not always successful, but they are far from doomed to a tragic fate.

Take, for instance, the grasslands in northern China, Mongolia, and Southern Siberia. State-run and private methods of resource management implemented in Russia and China are not nearly as effective in conservation as the traditional Mongolian group-property institutions. Around three-fourths of grassland in Russia, and more than one-third in China has shown signs of degradation, compared to just one-tenth of grasslands in Mongolia.

The water commons in Bali provide another example.

Subak, the traditional institution for irrigation management, has been sustainable for centuries without state regulation or private ownership. With water flowing downhill, the position of upstream farmers seemingly puts them in a prime position to free-ride. It is diverting more water for their own crops, but in reality, the opposite occurs. Farmers, upstream and downstream, are able to create a synchronized cropping arrangement in which damage from pests is minimized and downstream farmers retain access to water. In the end, crop yields are increased while water is used sustainably by all.

The voluminous literature on the commons documents countless similar examples. In the West, these include the cod fishery in Newfoundland (before it collapsed due to government mismanagement) and the lobster fishery in Maine. Digital and intellectual domains can fall under commons management as well. Wikipedia and the Creative Commons license exist only because people are able to cooperate and discourage free-riding.

Policymakers, unfortunately, sometimes fail to see the nuances of these sustainable systems.

Under “tragedy of the commons” assumptions (no communication, self-interested, rational agents, etc.), arrangements like those found in Mongolia and Bali simply can’t exist. As a result, technocrats, looking to promote sustainability and growth. It has often designed policies that backfire because they fail to take into account the complexity of local conditions.

Case in point:

Bali in the 1970s. On advice from the Asian Development Bank, the Indonesian government, in an attempt to boost crop yields, instructed farmers to plant rice as often as they could—disrupting the synchronized cropping schedule. Pest populations exploded as a result, and crop losses were massive. In this example, simplistic and detached development policy had disastrous consequences for the Balinese farmers.

Thus we see a genuine understanding of the commons is imperative for coherent policymaking. Scholars have long shown that Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons” is an inaccurate representation of reality. Policymakers ought to adopt a more realistic view of the commons, and professors should jettison this fallacious model from their Econ 101 courses. A failure to do this and embrace the real world would, indeed, be the real tragedy.

Written by Jimmy Chin

Jimmy is an undergraduate studying economics and Asian studies at UNC-Chapel Hill. He hopes to continue his studies in graduate school and has interests in economic development, political economy, and China. Other sources of enjoyment for him include reading philosophy, writing, and hiking.

Jimmy should study the way that our natural resources can be socially justly shared, by taxing the rent their use should generate. A natural resource is a God-created boon object for which nobody has the right to privatize. If we want access to it we should pay the community or government to cover what we are taking from it. This is normally the rent, which when taken as a tax results in a fair sharing and formal control of its accessibility. Even the seas should be included with international waters being rented from a world body.

Very nice article!

It leads me to another thought: Is “unsustainability” maybe a problem if the modern world?

You point on the fact that there is a natural behaviour in many regions of the world without external regulation.

Maybe this is due to the fact that sustainability in those regions is seen as a value in itself.

I think that a point which is often overlooked is the fact that the way we teach economics can change the way we think and see the world around us (in contrast to “hard sciences” as physics), and finally how we behave.

If students are tought that “unsustainable” behaviour is human nature it leads to a society where everyone behaves unsustainable. Everyone thinks “If everyone around me acts this way, why should I act differently?”

But as you write in your article this is not true. Now think of a society where students are tought sustainable behaviour is human nature. Would you act “unsustainable” when you know that you act against the “normal” behaviour? Would you like to feel as an outsider?

I’ve always thought of the tragedy of the commons as a pattern of human behavior that Hardin simply pointed out. Like any other human behavior, it can be changed. It’s not inevitable. There are situations where commons have been well managed (the ozone layer) and situations where they haven’t (overfishing, global warming). And Hardin does discuss some solutions in his essay, and Ostrom discussed some others. But I don’t see what removing all this from economics curriculum would accomplish. Given today’s environmental challenges, I think it’s a tremendously important topic to study.

Hunter gatherers managed the commons sustainably for 90% of human history. Non-capitalist agricultural societies managed the commons pretty sustainably for tens of thousands of years. Capitalism is in the process of destroying the commons in the blink of an eye. Hardin’s theories only relate to capitalist mismanagement of the commons. Capitalism is the tragedy.

Capitalists have been included in the category of land-owners, but they are something different and a lot more dangerous. Capital results from human labor to build or make something of value. Land value results from population density and people claiming the right to areas of natural resources that nobody has done anything to create. Its not the Capitalists to blame but the Landlords and they should pay for what they are taking and destroying what is there as a natural resource–a gift of God or at least of Nature, for the use of us all. If landlords must own sites and spoil them the least they can do is to pay a tax for the opportunities that they are withholding. TAX LAND NOT LABOR; TAX TAKINGS NOT MAKINGS!.