Most of us have an idea of how money came to be. It goes something like this: People wanted to exchange goods for other goods, but it was difficult to coordinate. So they started exchanging goods for money, and money for goods. This tells us that money is a medium of exchange. It’s a nice and simple story. The problem is that it may not be true. We may be understanding money entirely wrong.

A Different History of Money

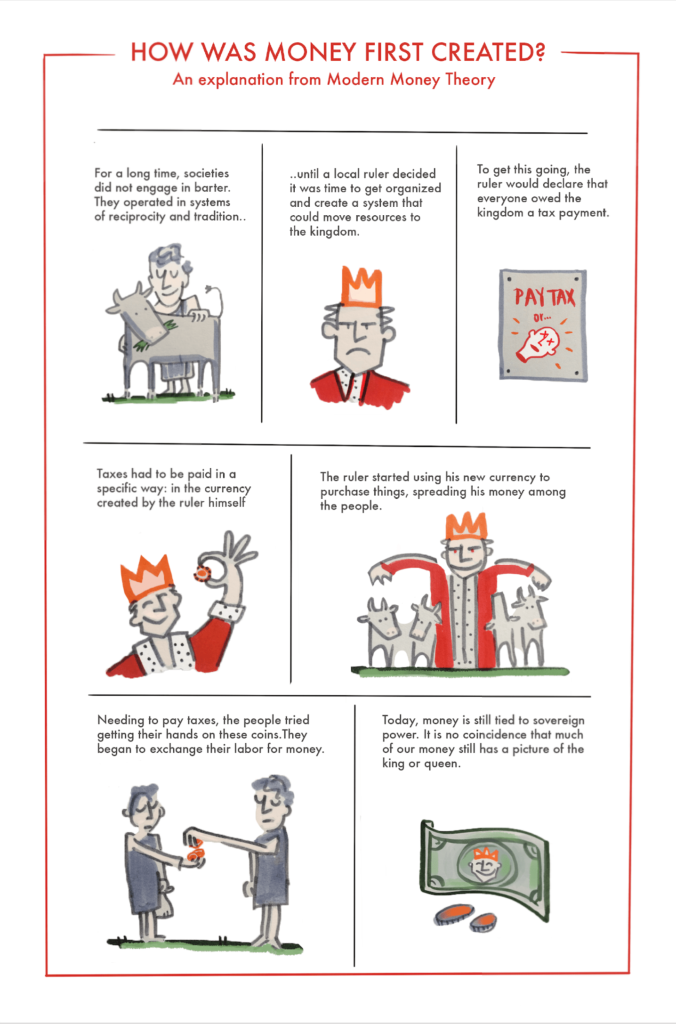

The above story assumes that first there was a market, and then people introduced money to make the market work better. But some people find this hard to believe. Those who subscribe to the Chartalist school of thought give a different history. Before money was used in markets, they say, it was used in primitive criminal justice systems. Money started as—and still is—a record of debt. It is a way to keep track of what one person owes another. There’s anthropological evidence to back up this view. Work by Innes, and Wray suggest that the origins of money are more like this:

In a pre-market, feudal society, there was usually a system to maintain justice in the community. If someone committed a crime, the authority, let’s call him the king, would decide that the criminal owed a fine to the victim. The fine could be a cow, a sheep, three chickens, depending on the crime. Until that cow was brought forward, the criminal was indebted to the victim. The king would record the criminal’s outstanding debt.

This system changed over time. Rather than paying fines to the victim, criminals were ordered to pay fines to the king. This way, resources were being moved to the king, who could coordinate their use for the benefit of the community as a whole. This was useful for the King, and for the development of the society. But the number of resources coming from a criminal here and there was not impressive. The system had to be expanded to draw more resources to the kingdom.

To expand the system, the king created debt records of his own. You can think of them as pieces of paper that say King-Owes-You. Next, he went to his citizens and demanded they give him the resources he wanted. If a citizen gave their cow to the king, the king would give the citizen some of his King-Owes-You papers. Now, a cow seems more useful than a piece of paper, so it seems silly that a citizen would agree to this. But the king had thought of a solution. To make sure everyone would want his King-Owes-You papers, he created a use for them.

He proclaimed that every so often, all citizens had to come forward to the kingdom. Each citizen would be in big trouble unless they could provide little pieces of paper that showed the king still owed them. In that case, the king would let the citizen go, and not owe them any longer. The citizen would be free to go off and acquire more King-Owes-You papers, to make sure he would be safe the next time, too. This way, all the citizens needed King-Owes-You papers to stay out of trouble. That made King-Owes-You papers widely accepted, and consequently, also a useful medium of exchange. This lead to the rise of markets.

This same pattern can be observed in more recent history. Matthew Forstater and Farley Grubb find that when European colonizers arrived in the New World, they wanted to get the local population to work. But when they offered them to work for a wage, the locals —who never saw a coin before— didn’t see the point. So then the Europeans decided that every hut had to pay them a certain amount of coins every so often in order to stay out of trouble. Now, having to make sure they could pay their tax to the authorities, working for a wage seemed like a good idea.

Not much has changed since then. Money can still be understood as a debt record or an IOU. In the US, we have dollars. Dollars are created by our version of a king: the government. We can understand them to be pieces of paper that say US Government-Owes-You. Just like the King in our story uses King-Owes-You papers to pay for resources, the US government uses dollars to pay for things that citizens provide. Rather than a cow, US citizens may supply a road, and receive dollars from the government as compensation. This means that now that they built a road, the government owes them. This is good for those citizens because when it’s tax day, that’s what they need. They give the government their dollars (which shows the government still owed them) and in exchange, the government doesn’t put them in jail.

Written and illustrated by Heske van Doornen

Well, thanks for the Forstater – Grubb links, but ……. having a hard time understanding the ‘history of money’ understanding that you seem trying to establish.

Is it that the history of money is a credit-debt relationship, more MMT-ish than either historical or Minskian in perspective.

Didn’t “Realms” issue coinage as money for 2500 years prior to the Colonies without any credit-debt relationship?

Didn’t they do this, more or less, to accomplish the exchange of goods (mostly) between holders of goods-wealth?

So, the history of money issuance was as a public ‘means-for-exchange’ to accommodate commerce, so to speak ?

Actually, Virginia’s late-coming to public ‘money’ issuance is a bad example of how the Colonies issued their monies, and most of the Colonies ‘money’ issuances had no credit-debt relationship.

For we Minsky lovers, I would recommend a leap-frog forward.

His wisdom is here galvanized in one of the less-popular, but most significant, of his Levy Institute writings.

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp127.pdf

I implore your understanding of Minsky’s conversion to Fisher’s public money construct.

Thank you.

.

Joe, the article is entirely consistent with the historical evidence of the origin of money as anthropologist David Graeber recounts in his BBC radio series “Promises promises a history of debt”. The particular relevant episode is here…

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b054423q

PS Graeber does make the point that money did change over the ages and across societies e.g. coinage superseded credits and debits for a period until the middle ages.

Very nice and impressive article.

I translated this article into Japanese.

http://whatsmoney.hateblo.jp/entry/2016/08/25/181301

But only one point, I don’t think that US dollar is desirable as a example of King-Owes-You, because FRB is not a federal institute but a cartel of private companies, you know.

Well, no it is not. The Fed Board of Governors is entirely made up of government employees. They oversee the interface between the Treasury (government) and the Fed regional banks (hybrid) and their dealings with private banks. Congress can withdraw the entire Act that created the Fed if it so chooses.

What you’re saying here simply isn’t true. The Federal Reserve is an independent agency of the United States government, like nearly two dozen other agencies. Its Board of Governors is nominated by the President and confirmed (or denied) by the US Senate. The Federal Reserve does charge interest, but it’s purely to cover operating costs and any revenue generated is by law handed over the the US Treasury. The sole private aspect of the entire system is that member banks get to own non-controlling stock in the 12 regional Fed banks. Emphasis on the non-controlling part; they have no formal say in operations.

I say formal because the entire system has gradually been corrupted and is riddled with conflicts of interest (it’s really one giant revolving door between the public and private sectors now). But that isn’t how it was designed to work. The Federal Reserve is not owned by private banks, much less foreign banks (which is a very common conspiracy theory).

Thanks Jurgen!

I think your on the track of just one of the reasons money came into existence,but you missed the main reason off ,Armies now raising a army in a perceived good cause to defend ones settlement has it limitations & has professional soldiering (although small) grew,it could be a short career,fighting for crops & food etc which could also decay well before a fair price was paid for ones deeds,may well not be delivered & even lands were often promised only to fail to materialise.

So money was created so soldiers could purchase,even pass on to there next of kin if killed which made soldiering & raising armies much easier,(particularly with a convent involved)although the coinage wasn’t standardised & therefore worthless particularly if you lost & often the king had to often raise money to either defend or attack,being killed in ancient battles is perceived as gallant & honourable but they still had to survive between battles & god help them in retirement! when they had given up accumulating,cultivating land!

Money goes back thousands of years & literally was made of false metals & worth,it was the standardisation of coinage that ended bartering & many local currencies & here we are in neoliberal mayhem,were sub currencies of dubious value are actually making a comeback,this is a sign that there is little if any real confidence in currencies as they stand

Hence why conscription,press ganging etc is likely to return they can’t pay for the deed they have undertaken to protect what isn’t worth protecting & raising a voluntary Army (which doesn’t mean unpaid) to do so is getting harder to forfil.

Raising of an army to protect the realm is but one example of the king drawing on the resources available in the kingdom for the collective good. Paying soldiers with coin doesn’t give the coin intrinsic value: something else must have made the coin worth acquiring first, which is the point of this excellent article.

Richard collective good is questionable,but the value was gained in the fact that the producer of goods market share grew, it bought in new customers/labour & encouraged division of labour & help the forming of bigger societies/markets,i agree value of coins were often very poor & this was proved when Britain standardised/regulated it coinage & weights and measures,its trade grew because they knew the coinage i)would purchased a set standard of goods ii) the value of the metals were true iii) that it could be used or readily exchanged much further afield because of number i which actually increased it value beyond its base value & help build the Empire on the back of this regulation. The intrinsic value was the benefit it gave both side of the equation i purchasing power ii knowing your produce wasn’t going to waste away without gain ,so cultivating & harvesting was more beneficial ,division of labour school teaching,nursery,soldiering encouraged humans to produce not just for themselves but for others who provided other services that help grow communities/societies & why after battles it was common to burn crops rather than offer them at market,i)because it forced up the price of what you the victor sent to market ii) it encouraged resources to move from about more (probably to the victors patch, markets growth depended on the people passing through,hence why river crossing grew,garrison towns,ports grew quicker from rather than is remote enclaves)but it also caused stagnation for millennia in the general economy i) the persistent tensions ii) money supply itself grew little to raise prices scarcity both natural & human made was advantageous & when you have some taking/getting very advantageous terms others are being disadvantaged. & that like today (although because of too much money or values not meeting the money supply)is why we are where we are today!it is rather more complicated because not just where money is created but how it gets to cross the equation is important!

That could seriously do with some punctuation, Ghost. It’s very hard to follow.

Whether your produce wastes away or not is entirely a function of whether you can find a buyer for it, not the method by which you manage the transaction.

Coins have never (or very rarely) been worth their face value in the metal they’re made from. They are a token. Before there were coins there were tally sticks and clay tablets to keep track of debts. Coins may have standardised the debt records, but you shouldn’t infer from this that the coins had intrinsic value. And it’s simply untrue that a coin’s purchasing power was fixed – no market has a “set standard of goods” that a coin will purchase. Price is based on supply and demand. It was ever thus.