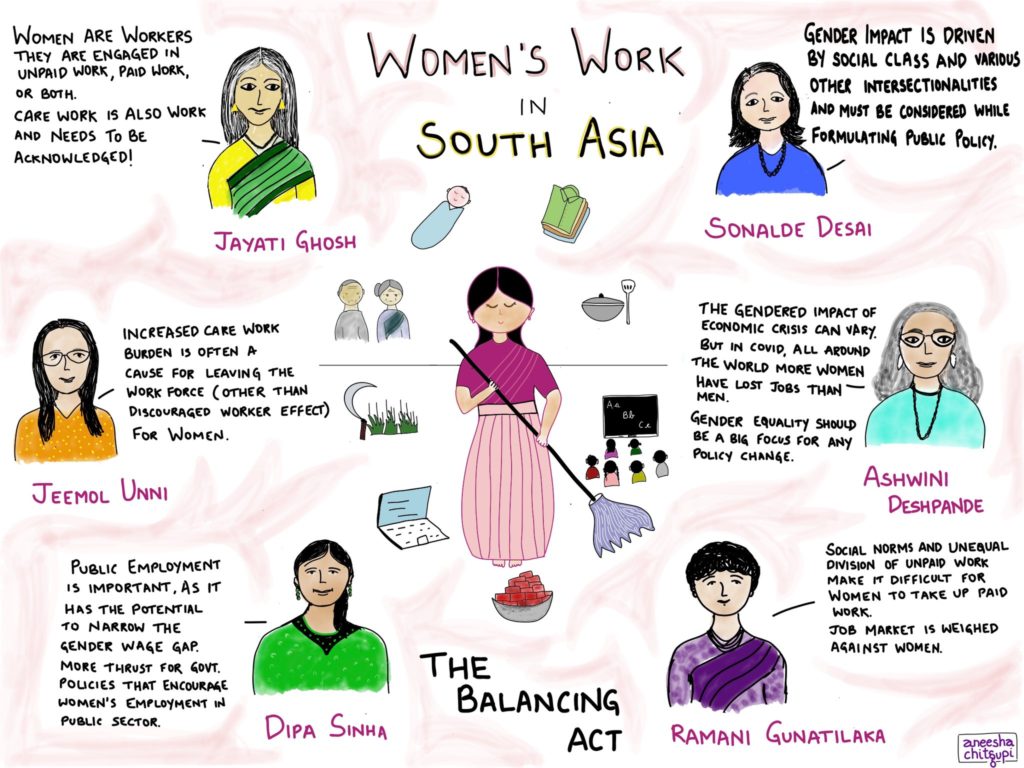

Although gender equality in employment is among the Sustainable Development Goals for South Asia, progress is hard to observe. Determined to explore why female employment levels remain low and stagnant, Varsha Gupta and Arun Balachandran of YSI’s South Asia Working Group organized a webinar series. Featuring eminent speakers such as Prof. Jayati Ghosh, Prof. Sonalde Desai, Prof. Jeemol Unni, Prof. Ashwini Deshpande, Dr. Dipa Sinha and Dr. Ramani Gunatilaka, the resulting conversations shed much-needed light on the topic.

Employment is a subset of work

The series began on May Day, with an inaugural session by Professor Jayati Ghosh. Highlighting the low female employment figures in India, she explained the difference between employment and work, the former being a subset of the latter. A major proportion of women are involved in work, though it is not paid and hence does not get counted as employment. The 2019 Time Use Survey in India reaffirms that women in India spend 2.5 times more time than men in unpaid activities. The gender wage gap exists and is high in private casual work. The Covid-19 pandemic has made things worse, furthering the case for gender-sensitive economic policies. View here

The impact of COVID-19

The second talk by Prof. Sonalde Desai focussed on employment trends during the Covid-19 pandemic. She presented the latest research with the use of Delhi Metropolitan Area survey (March 2019-20). The decline in employment occurred majorly in wage employment. With the use of econometric techniques, the research finds that in absolute terms, job loss for men was severe in the first wave of Covid-19, while the second surge hit women harder in the Delhi NCR region, India. The closure of schools and the consequent child rearing duties was one of the reasons that women’s wage work fell. Highly educated women were more affected than men. Rural areas absorbed the impact of the pandemic better than urban areas. The gender difference in impact was found to be highly dependent on the sector of employment and region. View here.

Informal workers bear the brunt

Jeemol Unni’s session concentrated on the impact of the Covid crisis on women and domestic violence among members of the informal workforce. Globally, pandemics harshly affect women more, due to the sectors and the kind of work women are involved in. The majority of the women form the bottom of the labor hierarchy. With the use of CMIE and NSS data, it is seen that the second wave of Covid-19 and lockdown affected women’s employment more vis-à-vis men. Discouraged worker effect is also visible among women. View here.

The COVID recession exacerbated trends

Prof. Ashwini Deshpande’s talk focussed on the gendered patterns in employment in India during first wave of the pandemic. The world over, the subsequent economic recession led to more unemployment among women than men, a pattern different from previous recessions. This is visible in India as well, in the 2020 CMIE data. The already gendered labor market in India, with fewer women employed, worsened further for females. Though the absolute figures for job loss are higher for men, the impact has been higher on women due to the pre-existing gaps. There has been exacerbating of women’s position in the domestic division of labor during August-December 2020. View here.

The potential of public employment

The penultimate session was featured Dr. Dipa Sinha highlighting the relevance of public employment in generating opportunities for female labor force in India. Nations with higher female LFPR are the ones which also have higher proportion of women in the public sector. In India, the NSS data shows that government is a significant employer for women. There is also sectoral concentration of women in health and education, where they are engaged as contractual or honorary workers (ASHA’s, Anganwadi Workers). Creating regular permanent positions in these sectors could encourage female employment. View here.

Education is not enough

Various facets of female employment in Sri Lanka were brought in by Dr. Ramani Gunatilaka from International Centre for Ethnic Studies, Colombo. While Srilankan women are better educated than their counterparts in other South Asian countries, they still remain disadvantaged in the labour market. As seen from a study led by Dr. Ramani on women’s activity preferences and time use, unpaid care and household work in Srilanka are mediated by social norms, and unequal division of unpaid work makes it difficult for women to take up paid work. View here.

Altogether, the webinars now form a virtual knowledge base on YSI’s YouTube Channel, making the insights available to young scholars all over the world.

About the organizers:

Arun Balachandran has a PhD in Economics from the University of Groningen, the Netherlands, in collaboration with the Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bengaluru. He is currently a Post-doctoral fellow at the University of Maryland, and serves as Coordinator of the YSI South Asia Working Group.

Varsha Gupta is a PhD student in Economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She using NSS data to assess issues of labor and gender, and serves as organizer for the YSI South Asia Working Group.

The YSI South Asia Working Group provides a platform for young scholars from South Asia -or those interested in the region- to select an issue they wish to work on, collaborate and discuss for better conceptualization of the problem and, debate, critique and improve upon solutions. We also invite scholars to suggest the most pressing problems and challenges to better guide the path for this working group. Join us!