Rapid technological change, if it is even happening, does not necessarily need to lead to mass unemployment or even major disruptions in people’s lives. In all cases, new technology is what society makes of it — that is, it should be used to broadly improve lives and work, not reorient the world around the technology itself or redistribute wealth upwards. Ride-hailing services like Uber and the promise of self-driving cars illustrate both sides of this point; polices like a job guarantee provide a path forward.

Illustration: Heske van Doornen

Don’t Be Afraid of Robots: Technology is What We Make of It

By Kevin Cashman

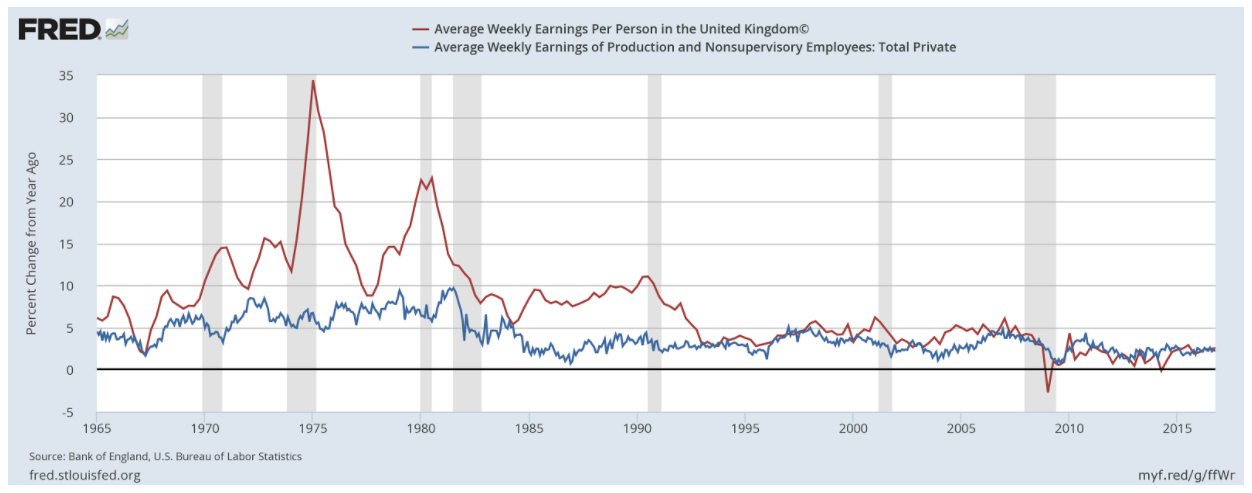

There is a lot of talk of the rapid development of technology leading to changes in the way people work as well as mass automation and thus mass unemployment. However, the data generally don’t support this story (the most recent data being a notable, but very limited, exception). Nevertheless, the story has currency among the public and politicians, in part due to the novelty and allure of technology — and the political power of its promoters. Throughout recent history, the promises of revolutionary technology have captivated imaginations but also come up far short. Instead of flying cars, there are apps for refrigerators and ordering cat food over the internet.

It is important to note that the gains from technological advancements do not necessarily need to go to the rich or lead to mass unemployment. If shared fairly, the gains could lead to social benefits, such as increased social services, and broad individual gains, such as more leisure time. And there can be concerted action to help those directly affected by technological change. While there are many policies that could be implemented, a job guarantee — where the government provides jobs to all those that need them — is the simplest and most straightforward way to deal with job loss. If people lose their jobs due to factors outside of their control, why not simply provide them with new jobs?

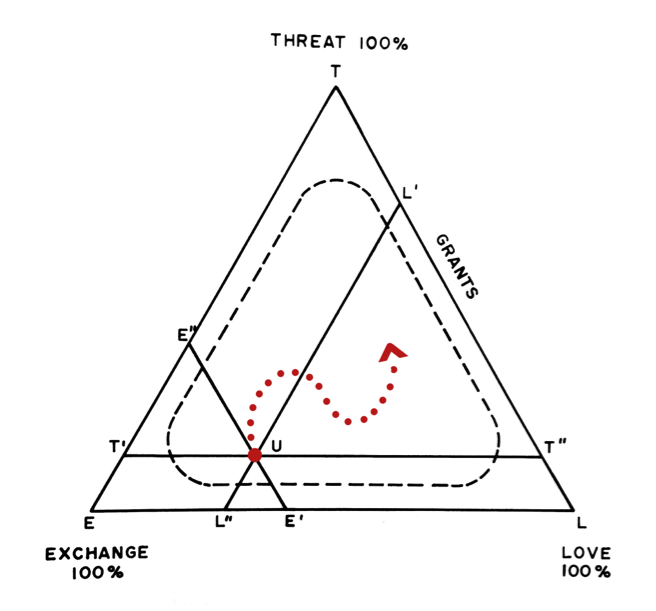

If the gains go to the top, it is important to point out that this is because of deliberate policy. It is not a natural outcome. The rich and their allies in politics promote this redistribution to the top as inevitable — as the “future of work,” for example — whether or not advancements in technology pan out or not. Since advancements in technology do not fundamentally necessitate a change in social relations, this is intentionally deceptive at worst and wishful thinking at best. To see this dynamic, looking at particular jobs and industries is instructive, for example, in taxis and buses and trucking.

The ability to use smartphones and the internet to mediate services is not particularly revolutionary or unique but it does provide some benefits. Uber, the ride-hailing company, brought investment and these ideas to the taxi industry and quickly took over a large part of the market, despite many issues with its service and sustainability. In Uber’s case, appealing to the political power of affluent residents in cities and the supposed innovation of its app was enough to negate its blatant disregard for regulations, questionable safety record, exploitation of drivers, and unprofitability. In this sense, Uber’s investment allowed it to provide some benefits to its relatively wealthy passengers at the expense of the disabled, regular taxi drivers, and others. Most importantly, because it subsidizes every ride (Uber loses money on every ride taken), it was able to undercut the regulated taxi industry. The government’s lack of interest in maintaining fairness in the taxi industry effectively led to Uber being handed the market.

How could this have been different? The taxi industry on a whole is not an industry with large margins or much investment. In part, this is due to underlying characteristics of the industry as well as regulation, including those aimed at limiting the number of taxis operating in a city (which is good policy). To realize the benefits of technology, taxi commissions or groups of taxi drivers in various places could have developed their own app and infrastructure to facilitate ordering of cabs on the internet. This would have required substantial organization and money, which could have been facilitated and provided, respectively, by the government. The result could have been an app that allowed taxi authorities to continue to maintain standards for safety and operation and also provide the seamless service that certain groups of consumers desire. Indeed, competitor apps are being developed this way and existed before Uber, but they must now claw market share away from Uber. This is quite difficult because Uber is still subsidizing rides and keeping prices artificially low.

Let us now assume that rapid technological advancement is inevitable: self-driving cars and buses are finally right around the corner, as has been promised for years. (Indeed society could be on the cusp of this sort of technology, although the challenges shouldn’t be understated.) There would be massive benefits if self-driving vehicles are implemented successfully: increased mobility for the elderly, many fewer accidents, lower operating costs, increased productivity when in transit, etc.

Along with these benefits, there would be significant disruptions to the labor market. Ideas around how to approach these changes were discussed in a recent report, Stick Shift: Autonomous Vehicles, Driving Jobs, and the Future of Work.1 It discusses two questions that are central to evaluation rapid disruptions to the labor market: How fast will the technology develop? How much of an impact will it have?

Regarding the first question, and assuming that these technological hurdles are overcome,2 the report notes:

If the technology is successfully developed, the rate of the adoption and popularization of autonomous vehicles will depend greatly on whether necessary infrastructure is built, and whether and how regulation responds to these advances in technology. One of the inevitable debates will be between those who wish to ensure that autonomous vehicles are safe and reliable and those who want to get them to market as soon as possible. The outcome of this debate could greatly determine how the labor market is affected. Thorough vetting of the technology, along with phased rollouts, would allow time for workers to adjust to incoming shocks, and would dampen those shocks as well.

If the government were to assume the costs of building infrastructure for self-driving vehicles instead of the companies that are selling them, it would be fair for the government to also take a pro-active approach and develop a process to adequately assess the safety of those vehicles. This would somewhat mitigate the effects on the taxi industry and on bus drivers, especially in the early years of their use.

Proponents of self-driving vehicles also often forget to mention that technology will replace individual activities of workers but not necessarily all of the activities that encompass their jobs. Truckers, for instance, perform many other activities besides simply driving:

…in the trucking industry, there are many tasks that are difficult to imagine autonomous-vehicle technology being able to manage, which may limit their adoption or consign them or the driver to a secondary role. This includes many things that truck drivers are required to know, such as how to inspect the vehicle and cargo, perform maintenance and fix emergency problems, put on tire chains and deal with unpredictable weather, refuel the vehicle safely, and carry dangerous materials safely, to name a few.

If self-driving trucks took over the trucking industry, this suggests there would be many more support jobs in the trucking industry.

The other question is more pertinent considering our assumptions. How much of an impact technology will have on society is entirely up to society. The question is then not how much of an impact will self-driving cars have on society but where does society need self-driving cars and how do self-driving cars fit with social goals? There is a convincing argument that cars — self-driving or not — should have much less of a role in cities in the future. While taxis could have a role to play in the future, for example, public transportation and good urban design should be the focus, thus eliminating much of the need for taxis. In this vein, employment in the taxi industry could decline, but in addition to more social benefits from less vehicle use, employment would increase in association with an increase in investment in public transportation.

The social aspects of occupations are also important to consider when asking whether it might be desirable to transition to self-driving vehicles:

There is also the question of more socially oriented driving jobs. Bus drivers are one example. City bus drivers preserve order and safety on buses, provide information, ensure payment, and are generally considered community members and authority figures. School bus drivers have specific responsibilities related to the safety of the children they supervise. For these reasons, it may not be desirable or necessary to replace bus drivers, completely at least, even if the buses were fully autonomous.

In this sense, the elimination of these jobs would be akin to cuts in public services, and they would also eliminate some social benefits. Social aspects of jobs are rarely considered — but they are very important.

Here, a jobs guarantee would be useful, since it is a policy that prioritizes the social aspects of jobs and since social benefits are not prioritized in the private job market. Returning to the example of bus drivers, buses could be self-driving in the future but the “driver” need not be replaced. Rather, the position could be reoriented in a purely social role.

Whether technology will bring small changes, as in the case of Uber, or large changes, as in the case of self-driving vehicles, who benefits is entirely up to society. Gains from technology can be shared broadly with the right policies — just a few of which were described here — so there is no need to inherently fear the robots. A jobs guarantee is one of those policies, and it is perhaps the most important. (And it’s gaining traction in the mainstream.) A broad coalition, focused on the appropriate use of technology and promoting a job guarantee, could keep the actual threat — those wanting to harness the benefits of technology for themselves — at bay. Whether or not robots and mass automation are around the corner, it’s good policy, too.