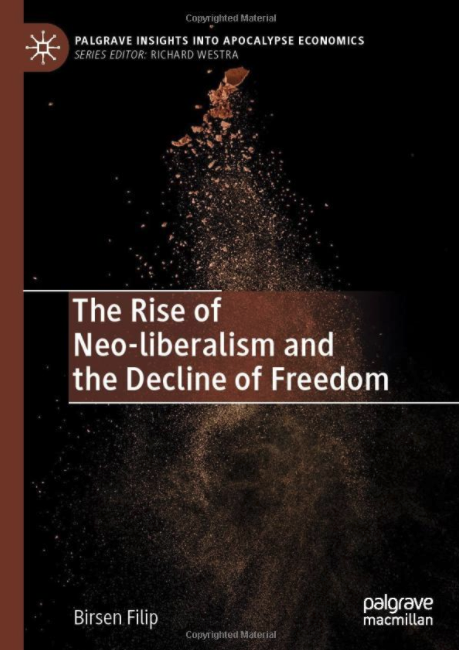

In her book fellow YSI member Birsen Filip makes an important and timely contribution by telling the story of neoliberalism and its dramatic rise over the past four decades. She traces its impact on our contemporary way of living, thinking, and being and in so doing demonstrates its elevation to a near law of nature that permeates nearly every aspect of our society. Many of us will be familiar with many aspects she touches upon, but it is galvanizing to see how deeply neo-liberal thinking has penetrated and reshaped our way of being.

Birsen starts by expounding the pillar upon which neo-liberal thinking rests: negative freedom (chapters 2 and 3). Friedrich Hayek and Friedman developed the idea of negative freedom by defining it as ‘freedom from coercion’ – the liberty to consume, produce and exchange voluntarily – which stands in contrast to positive freedom (i.e. improving individual self-determination by investing in individuals, communities, environments by the government). It purports that economic freedom in the marketplace (‘freedom to choose’) is a precondition for political and civic freedom (‘right to assembly, freedom of speech, freedom of religion’ etc). A threat or coercion on economic freedom would mean an infringement on political freedom as well. This expresses itself in the primacy of the marketplace, free individual choice, free fluctuation of prices and not allowing the government or any central entity to infringe on this economic freedom for an apparent collective good (freedom from coercion).

How this concept of freedom limits the scope of government is treated in chapter 4. Chapter 5 treats the rise of transnational corporations which have been able to take advantage of an ever-increasing scope of the market. In chapters 6 and 7 we vividly see the effect of mass consumption culture on the environment. How private interest stands over public interest in innovation policies is described in chapter 8. Chapter 9 and 10 illustrate the decline of unions and organized labor and the rise of inequality, and chapter 11 the decline of moral and ethical values. In chapter 12, Birsen returns to the realm of ideas to show how neo-liberal thinking has become entrenched with the academy.

At the core of the book’s message, Birsen demonstrates a disastrous paradox: the supposed freedom which neo-liberalism promotes is indeed a trap. What Birsen describes is a vortex in which more and more spheres of our lives become caught in. ‘Freedom from’ indeed is not indeed liberating. On the contrary, it is contributing to the decline of freedom; it imprisons and destroys our capacity for imagining alternative pathways and collective action and in doing so it destroys our ability as individuals and societies to confront our problems. We can all sense the writing on that wall, namely the steady decline and destruction of societies and our environment, and yes, of individual freedom.

What the book offers is how deeply neo-liberal ideas have taken hold of our thinking and penetrated how we perceive ourselves as individuals, how we relate with others. Moreso, it offers a glimpse of how we are eroding our social fabric and destroying our environment by extending the sphere of the market to nearly anything and exploiting the resources of our environment. More deeply it also sheds light on the current malaise and inability to address our global challenges since neo-liberal thinking discounts the ability of collective action (state and unions).

Birsen offers a hopeful plea that recognizing these entrappings which we all intuitively sense may help lead to a change in mindset and an affirmation vision of our global society and the environment in which we live: Positive freedom.

Birsen Filip holds a Ph.D. in philosophy and master’s degrees in economics and philosophy. She has published numerous articles and chapters on a range of topics, including political philosophy, geopolitics, and the history of economic thought, with a focus on the Austrian School of Economics and the German Historical School of Economics.

BUY THE BOOK

Jay Pocklington is the Manager of the Institute for New Economic Thinking’s Young Scholars Initiative (YSI). He received B.Sc. and M.Sc degrees in economics from Freie Universität Berlin.

believed to be a distinct system with its own logic that requires experts to manage it.” Their work carefully explains why our current system is an econocracy and discusses possible ways to change that. Based on my own experiences so far, I can’t help but agree with them.

believed to be a distinct system with its own logic that requires experts to manage it.” Their work carefully explains why our current system is an econocracy and discusses possible ways to change that. Based on my own experiences so far, I can’t help but agree with them.