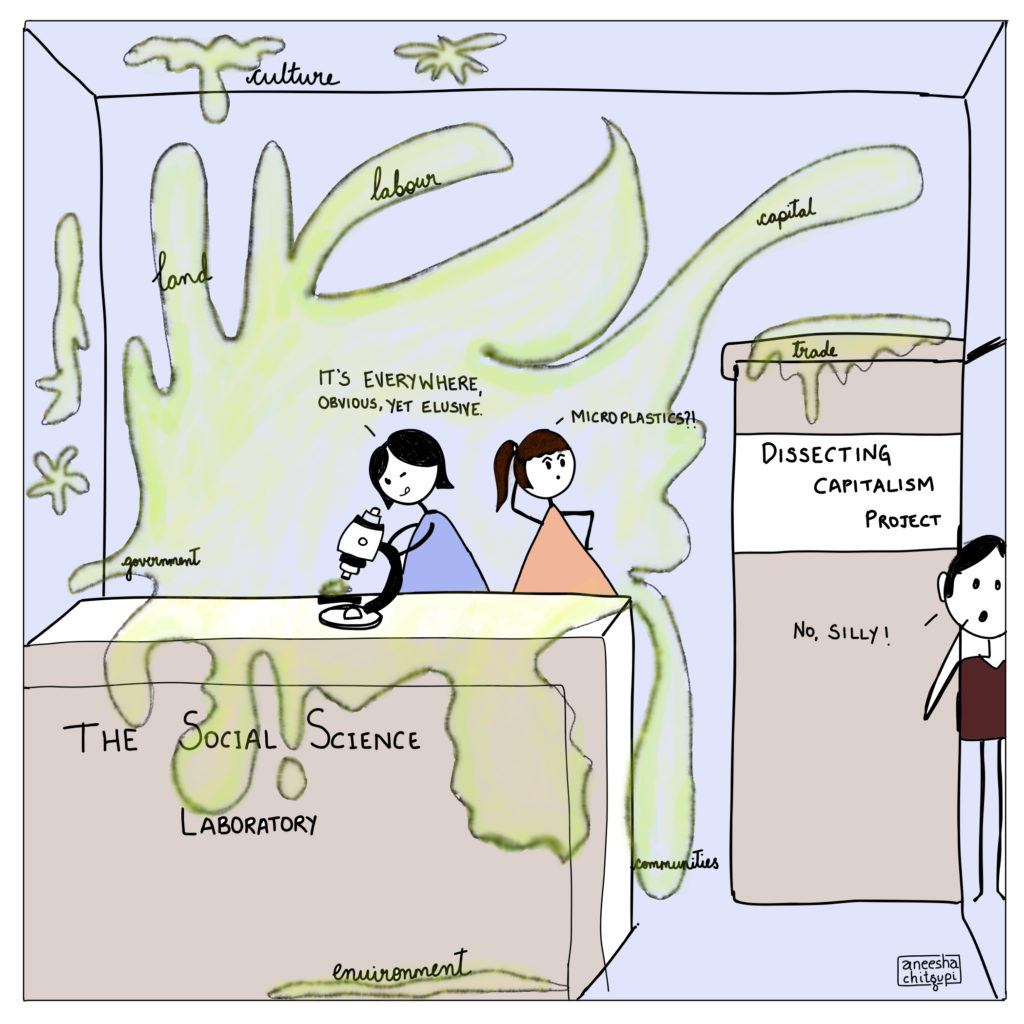

By Shyam Soundararajan | Dissecting Capitalism is a recurring webinar series in the South Asia Working Group that aims to organize a webinar series on the dominant ideology/economic system – capitalism. It aims to explore the tenets of capitalism over the fabric of time and examine its influence on the economy and social classes.

Over the course of 8 webinar sessions in November and December 2021, this project has brought together scholars from various fields of academia such as economics, philosophy, social policy, and law to dissect capitalism through their unique theoretical and empirical lenses. This webinar series was organized by Sattwick Dey Biswas, Aneesha Chitgupi, and Shyam Soundararajan.

Before YSI South Asia hosts Season II of Dissecting Capitalism: Its past, present and future, here is a snapshot of the topics covered under Season I

1. Globalization as a Threat to Democracy

The introductory session of the Webinar Series featured Professor Daniel W. Bromley, a Professor of Applied Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This session was centered on globalization, international trade and democracy and was based on the book, “Possessive Individualism: A Crisis of Capitalism”.

Through this session, Professor Bromley was able to provide an interactive lecture on why globalization is a threat to democratic coherence. Through this lecture, Professor Bromley was able to unveil and demonstrate the hidden reality that globalization weakens the ability of national governments to confront economic crises.

Overall, this session displayed the problems that capitalism has imposed upon national governments, namely the inability to confront economic problems due to the issue of losing “global competitiveness”. View here

2. Multidimensional Poverty around the world: Unmasking Disparities

This session featured Dr. Sabina Alkire, the Director of the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative at the University of Oxford. This session was centered around the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), which measures poverty using a variety of factors.

Through this webinar, Dr. Alkire was able to explain more about the MPI by explaining its methodology. After this, Dr. Alkire presented the findings of the October 2021 global MPI report. In addition to this, Dr. Alkire discussed and dissected various disparities across ethnic groups and populations.

Overall, this webinar presented the impact of capitalism and its various endemic traits on poverty around the world. By discussing the MPI, Dr. Alkire was able to demonstrate how capitalism actively contributes to major poverty trends around the world. View here

3. Compressed Capitalism and Late Development in India

This session featured Professor Dr. Anthony P. D’Costa, an Eminent Scholar in Global Studies and Professor of Economics at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. This session was centered around the changes faced by the Indian economy and the population following the 1991 economic reforms.

Through this session, Professor D’Costa presented an alternative approach to understanding the development dynamic of India. Through the use of capitalist dynamics in developing countries and compressed capitalism, Professor D’Costa showed that wealth inequality present in India is an inherent trait of late capitalist societies.

Overall, this session explained how some of the defining flaws of a capitalist society in a developing country are not an anomaly but rather a key tenet of a late capitalist society. The findings discussed in this session led to a broader understanding of some key tenets of capitalism. View here.

4. Designing a Pro-Market Social Protection System: A Literature Review

This session featured Professor Dr. Einar Øverbye, a Professor in International Social Welfare and Health Policy at Oslo Metropolitan University. This session was centered around the common argument that the welfare state is detrimental to the economy as it disincentivizes work.

Through this session, Professor Øverbye was able to explain and deconstruct the arguments surrounding the idea of welfare states disincentivizing work and reducing efficiency. By deconstructing the disincentive argument, Professor Øverbye was able to put forward his argument in support of designing a pro-market social protection system. Moreover, Professor Øverbye was able to demonstrate the importance of good design in a social system, thus unraveling the challenge surrounding the construction of a pro-market social protection system.

Overall, this session explained how good design in social structures can overcome some fundamental flaws associated with a system. This session also covered the role of a welfare state in a capitalist society and was able to discuss the contribution of key tenets of capitalism to a pro-market social protection system. View here.

5. The Law is an Anagram of Wealth

This session featured Professor Dr. Benjamin Davy, a visiting professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Johannesburg, and the School of Architecture and Spatial Planning, TU Wien University. Based on the book, “Land Policy”, this session addressed the relationship between land uses, land value, and land law.

Professor Davy was able to explain and demonstrate how the concept of material wealth depends heavily on the legal system present in a country. By using land laws and values, Professor Davy was able to explain how the economic structure of a society is affected by the law, thus leading back to the title of the session

Overall, this session showed attendees how material wealth, a key component of capitalism, depends on the legal system of a country. This inter-disciplinary session was also able to display the link between two seemingly unrelated fields of the social sciences, namely economics and law. View here.

6. John Stuart Mill’s Imperialism, Protestant Work Ethic, & Global South

This session featured Professor Dr. Elizabeth Anderson, the John Dewey Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy and Women’s & Gender Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. This session was co-organized with Diana Soeiro, an organizer at the Philosophy of Economics Working Group. This session was based on the core ideas of Professor Anderson’s upcoming book, which is focused on the history of the Protestant work ethic through the history of economics.

Through this session, Professor Anderson was able to show how John Stuart Mill’s economic theories on workers and his liberal ideas were contradictory to his stance on Imperialism. Professor Anderson was able to trace Mill’s contradictions to tensions innate to the Protestant work ethic. By doing this, Professor Anderson was able to transition to a more global discussion of the Protestant work ethic, which would be able to address the challenges faced by workers in the Global South in today’s economy.

Overall, this session presented yet another interdisciplinary focus on capitalism through philosophy and work ethic. By linking Mill’s contrarian positions to tensions in the Protestant work ethic and by globalizing the topic to factor in worker challenges in the Global South, Professor Anderson was able to provide some key insights on the often-ignored role of work ethic and philosophy in capitalism and globalization. View here.

7. Why Poverty is More Than a Lack of Income: Thoughts from China

This session featured Professor Dr. Robert Walker MBE, Professor at the Institute of Social Management/School of Sociology, Beijing Normal University under China’s ‘High-Level Foreign Talents’ program. This session was centred around the contemporary understanding of poverty beyond income and the case of China, which attempted to eradicate poverty in the 2010s.

Through this session, Professor Walker was able to highlight the disparity between policy and political reality when it comes to the concept of poverty.

By including the case of China, which eliminated absolute poverty to discover the presence of relative poverty, Professor Walker was able to shift the argument of poverty beyond the idea of low income and was able to provide psychological insights on poverty.

Overall, this session presented the need to rethink the mainstream understanding of poverty. Discussions surrounding China’s attempts to eradicate poverty presented an undocumented side of China affected by the country’s shift towards a semi-capitalist society. This session also provided an interdisciplinary outlook on poverty in China, which allowed attendees from the South Asia Working Group to be cognizant of poverty conditions in other Asian regions. View here

8. Beyond False Dilemmas in Economic Policy

The final session of the first season featured Dr. Sanjay G. Reddy, Associate Professor of Economics at The New School for Social Research. This session was centred around the discussion of false dilemmas in economic policy.

Through this session, Dr. Reddy was able to present his economic argument for dissolving and dismissing false dilemmas rather than resolving them. By using the false dilemmas of “for or against growth” and “domestic markets or globalization”, Dr. Reddy proved the logical fallacy in such dilemmas and presented alternative questions that were worth pursuing.

Overall, this session provided closure for the first season of “Dissecting Capitalism” by discussing false dilemma, a prominent element found in the discourse and dialogue surrounding capitalism and the need to rethink it. By discussing the “for or against growth” dilemma, Dr. Reddy was able to discuss a core argument presented by people opposing the need to rethink capitalism. Ultimately, this session allowed the attendees to dissect capitalism through the notion of false dilemmas present in today’s economic world. View here

Over the course of 8 webinar series held across 2 months, the South Asia Working Group was able to embark on a journey of exploration, learning and profound thinking. Moreover, the attendees were able to actively discuss core ideas of capitalism and dissect capitalist structures and norms, which enhanced discussion within the working group.

While this season did cover mainstream ideas of capitalism and other economic factors that are affected by capitalism, it did not cover the link between capitalism and heterodox fields such as climate economics and agricultural economics. This is something that Season II aims to cover. With a wide range of topics from economic thought to climate change to legal theory, Season II aims to build upon the foundations of the first season and further continue to explore the tenets of capitalism.

Season II will feature Jayati Ghosh, Barbara Harris-White, Shailaja Fennell, Katharina Pistor, and K V Subramanian. Join us live!

Register now

The YSI South Asia Working Group provides a platform for young scholars from South Asia -or those interested in the region- to select an issue they wish to work on, collaborate and discuss for better conceptualization of the problem and, debate, critique and improve upon solutions. We also invite scholars to suggest the most pressing problems and challenges to better guide the path for this working group. Join us!

About the organizers:

Sattwick Dey Biswas is an affiliated Research Fellow at the Institute of Public Policy, Bangalore, India. In 2019, he has earned Doctor rerum politicarum at the School of Spatial Planning, TU Dortmund University, Germany. He has published his doctoral thesis as a book titled, “Land acquisition and compensation in India: Mysteries of valuation” (2020) with Palgrave Macmillan. He is interested in the areas of Land Policy, Social Policy, and Political Economy.

Shyam Soundararajan is a high school student from Dubai, UAE. His research interests include economic development, poverty and wealth inequality. He has published articles in the Harvard International Review and has contributed vastly to his school’s social science curriculum. Shyam aspires to major in Mathematical Economics with a minor in South Asian Studies.

Aneesha Chitgupi is a research fellow at the XKDR-Forum -Chennai Mathematical Institute. She received her PhD in 2020 from Institute for Social and Economic Change affiliated to University of Mysore. Her thesis analysed the economic determinants of India’s external stabilisation under the balance of payments framework. Her current research interests are public finance, government debt and liabilities management.