The main takeaway from the French presidential election is that criticism of the European Union (EU), including the eurozone, is not well received regardless of its validity. While Europe might currently be breathing a sigh of relief, the strategy of silencing and ridiculing those who express dissatisfaction with EU policies is dangerous for its future.

Presidential campaigns in France

During the campaign for the first round of the French presidential election, two candidates touted the possibility of leaving the euro: Jean-Luc Mélenchon, representing the leftist France Insoumise party, and Marine Le Pen from the extreme right-wing Front National. Most outlets considered their attacks on the euro to be a political liability with the mainstream electorate. The media slotted both candidates as “anti-European” extremists that should be feared. However, a closer look at the platforms of these two reveals that their critiques of the EU and their desired outcomes bear very few similarities.

Marine Le Pen promised a “France-first” approach and pledged to pull France out of the eurozone and close the country’s borders. Her platform plays on racism and xenophobia, and blames France’s woes on immigrants. It is important to note that she did propose strengthening the welfare state and extending benefits, but only for French people and not foreigners.

Mélenchon’s take on the EU was very different. His platform’s “Plan A” was to push for EU-wide reforms that aimed at bringing growth and strengthening mutual support amongst member states. He criticized the EU for becoming a place ruled by banks and finance, and his goal was to leverage France’s influence within the bloc to end austerity policies in all member states. If these negotiations with other EU members failed, then there was a “Plan B” that called for France to leave the euro and the EU in order to pursue a stimulus plan, which is not permitted under the deficit limits imposed by current EU regulation.

A large part of the media coverage received by Mélenchon centered on personal attacks, rather than on providing an accurate overview of his policies. He was accused of being a communist, both an admirer of Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez, and a Russia sympathizer. With a significant social media following and energizing campaign, Mélenchon was able to surge in the polls late in the race. However, he did not manage to garner sufficient support to qualify for the second round of the election.

Plagued by scandals and voters’ discontent with the current administration, the candidates backed by the two traditionally mainstream parties in France, the Republicans and Socialists, did not make it past the first round. The run-off election will take place on May 7th between Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron.

Dubbed the establishment’s anti-establishment candidate, Macron describes himself as a staunchly pro-EU, pro-immigration, and pro-globalization centrist. Macron is backed by the party he created in 2016, “En Marche!,” and is successfully managing to brand himself as an outsider candidate. However, it should not be forgotten that as an economy minister in Francois Hollande’s government, who did not seek re-election due to extremely low approval rates, Macron was the architect of labor market reforms that weakened protections for workers and favored businesses. A close look at his program reveals his policies are strikingly similar to those of Hollande, just with different branding and rhetoric.

Macron’s platform consists of neoliberal platitudes that espouse values such as tolerance and acceptance of immigrants, while advocating for austerity and dismantling of social protections under the guise of increasing efficiency and “modernizing” the French economy. Macron pledged to reduce France’s deficit below 3 percent, as mandated by the EU, while also cutting taxes. To achieve both goals, Macron would undoubtedly have to slash government spending, which would most likely have a negative impact on the economy overall.

Macron’s uncritical embrace of the EU has gained him the praise and endorsement of other European leaders. Global financial markets that are reassured by his pro-EU stance are also celebrating the prospect of his victory. While his commitment to structural reforms and budget cuts is likely to please Germany and the European Commission, the question is if he can also satisfy the people of France.

Polls suggest that Macron will now win the run-off against Le Pen. However, concerns are mounting that if his government fails to deliver, the far right will be strengthened by the following election. Given how similar Macron and Hollande’s programs are (despite the different packaging) they are unlikely to deliver a different result.

The failed economic policies of the EU

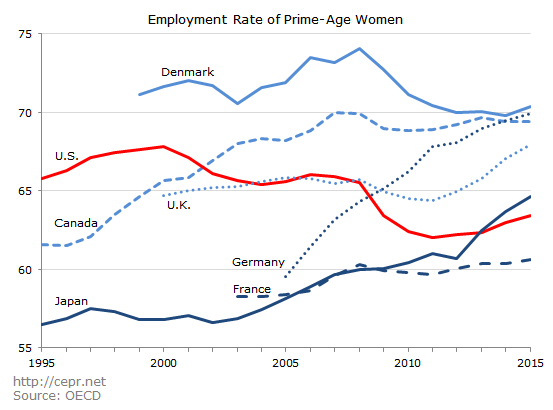

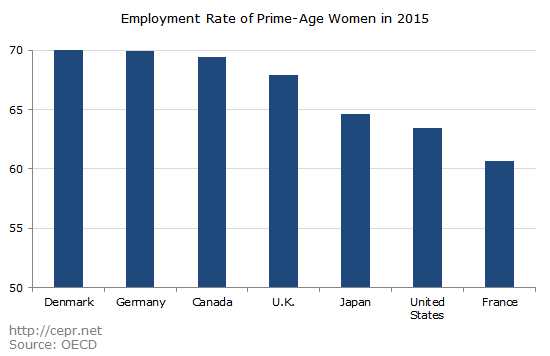

The French economy struggles with high unemployment rates, particularly for young people, and is facing a decade of economic stagnation. Under increased pressure from the EU for France to abide by its deficit rules and reduce spending, previous governments have implemented harsh pension and labor reforms. These measures have failed to jumpstart the economy, and it seems intuitive that France should pursue different policies that could actually provide the much needed stimulus to its economy.

It’s not just France that is stagnating. Since the 2008 crisis, the entire Eurozone has seen a slow and uneven recovery. Particularly, the worst hit countries such as Greece, Italy, and Spain, are still dealing with the consequences of shrinking incomes and high unemployment. Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz showed how the structure and design of the euro were a key factors in holding back the recovery of the EU.

The structure of the euro was established by the Maastricht Treaty which laid down the groundwork for how the EU and the euro area ought to be set-up institutionally. The treaty arbitrarily established yearly deficit limits for countries at 3 percent of GDP. After the crisis, the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union expanded the influence of the European Commission, an unelected body, to impose policies on member states. EU institutions have used the deficit limit as justification to dictate a neoliberal agenda, characterized by imposing austerity measures and pro-business structural reforms on member states, with very little consideration on the worsening of unemployment, poverty, and other social indicators.

Considering the shortcomings of neoliberal policies imposed by the EU, perhaps Melélnchon’s “Plan A,” to push for EU-wide reform is not that “extremist” after all. Rather than crucifying him, he should have been given the chance to advocate for reform. The current direction taken by the EU is one that through austerity measures is slowly dismantling the European Social Model, which has traditionally been characterized by a strong safety net.

What the future holds

As long as the EU imposes and encourages a platform that hurts people, far right politicians like Marine Le Pen will continue to tap into those anxieties and gain popularity. The success of the Brexit campaign should serve as impetus for the EU to reevaluate its policies.

Politicians like Macron, who chose to ignore the flaws of the eurozone and advocate for more of the same unsuccessful policies may win popularity now, but set themselves up for failure in the long run. Macron’s unconditional praise of the EU’s virtues is somewhat similar to Hillary Clinton, who under a backdrop of suffering and social crisis, responded to Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again,” by stating “America is already great!” This strategy failed and Clinton lost, with areas where jobs were under the most severe threats swinging towards Trump.

For the European project to succeed and continue bringing peace and unity to Europe, economic policy reform is necessary and austerity needs to end. Ignoring the economic struggles of the bloc and refusing to recognize the role of EU policy in exacerbating them will continue to fuel the rise of extremist right wing politicians. Calling those who advocate for socially inclusive reforms “extremists” is a strategy bound to backfire.