By Nikos Bourtzis.

Much of the developed world has experienced stubbornly low real wage growth since the financial crisis of 2007. Currently, the British people are seeing their earnings decline in real terms. Even in Germany, where unemployment keeps falling to record lows, wage growth is stagnating. This phenomenon has squeezed living standards and has been one of the main culprits behind the rise of anti-establishment movements. Faster pay rises are desperately needed for the global recovery to accelerate and for ordinary people to actually be a part of it. This piece explains why rising labor compensation has been relatively minuscule during the current economic upturn and how this phenomenon could be remedied.

A bit of history

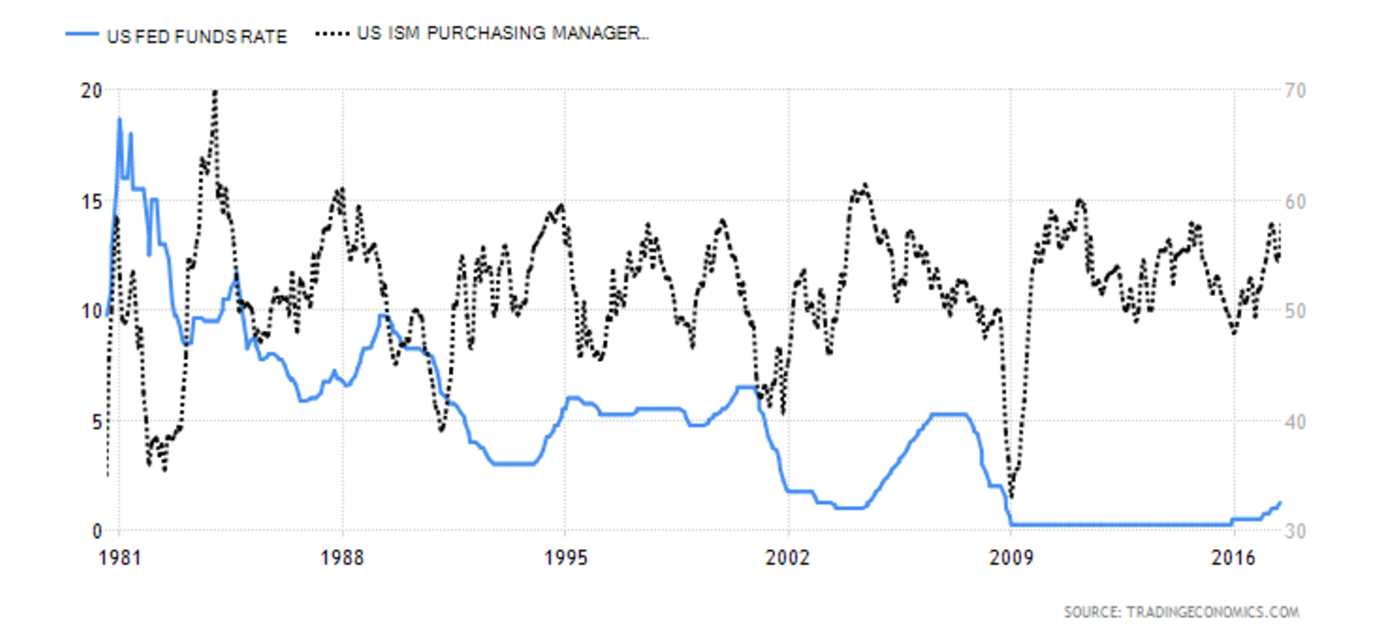

The lack of meaningful pay rises is not a phenomenon that started with the financial crisis of 2007. It can be traced back to the 1970s and 1980s, when monetarism started sweeping into academia and politics. The stagflation of the 1970s, the simultaneous rise of inflation and unemployment, led some governments to abandon the Keynesian policies of the past because apparently these policies could not deal with the stagflation. Monetary policy became the preferred tool to control inflation, together with a revived notion that markets, if left to their own devices, would bring the best social outcomes. The Thatcher and Reagan governments are some of the most famous examples of States adopting and implementing these beliefs. The first institution targeted for deregulation was the labor market. Wages increases were frozen and employment protection was scaled back, because it was believed that demand and supply forces would restore full employment. However, unemployment in the UK exploded after Thatcher came into office in 1980, increasing to over 10% and never returning to its post-World War II lows of between 1% and 2%.

Labor unions are one of the most important institutions regarding pay rises. In most industrial countries, they are responsible for wage and working conditions negotiations between employers and employees. Union membership in OECD countries grew until the mid-1970s but then started dropping. With the rise of neoliberal governments in the West, organized labor came under attack. Under the free-market ideology, unions disrupt economic activity with strikes and demand higher-than-optimal wages. Thus, their power needed to be kept in check. What is more important, though, is the shifting of ideas in what the goals of the State should be. In the post-War period, an expressed purpose of governments was to keep aggregate demand at full employment levels. The UK government, for example, stated full employment as its purpose after the War in its Economic Policy White Paper in 1944. That goal changed with the rise of neoliberalism.

When the commitment to keep employment levels high and stable was abandoned, and labor markets were deregulated, unemployment spiked in most countries and has never fallen at levels where it can be stated that full employment exists. Even during strong upturns unemployment levels in most countries did not dip below 4%. As a result, labor unions, and workers in general have lost their biggest bargaining chip. When there is full employment, and thus jobs are abundant, workers have more power to demand higher wages and better working conditions. With the neoliberal policies of the Reagan administration, real wages in the US got decoupled from productivity, meaning that workers stopped receiving their fair share of the output produced. The same phenomenon has been observed in many other industrialized countries, such as the UK. The policies introduced in the 1980s were pretty much sustained and expanded up until 2008.

The Financial Crisis: A turn for the worse

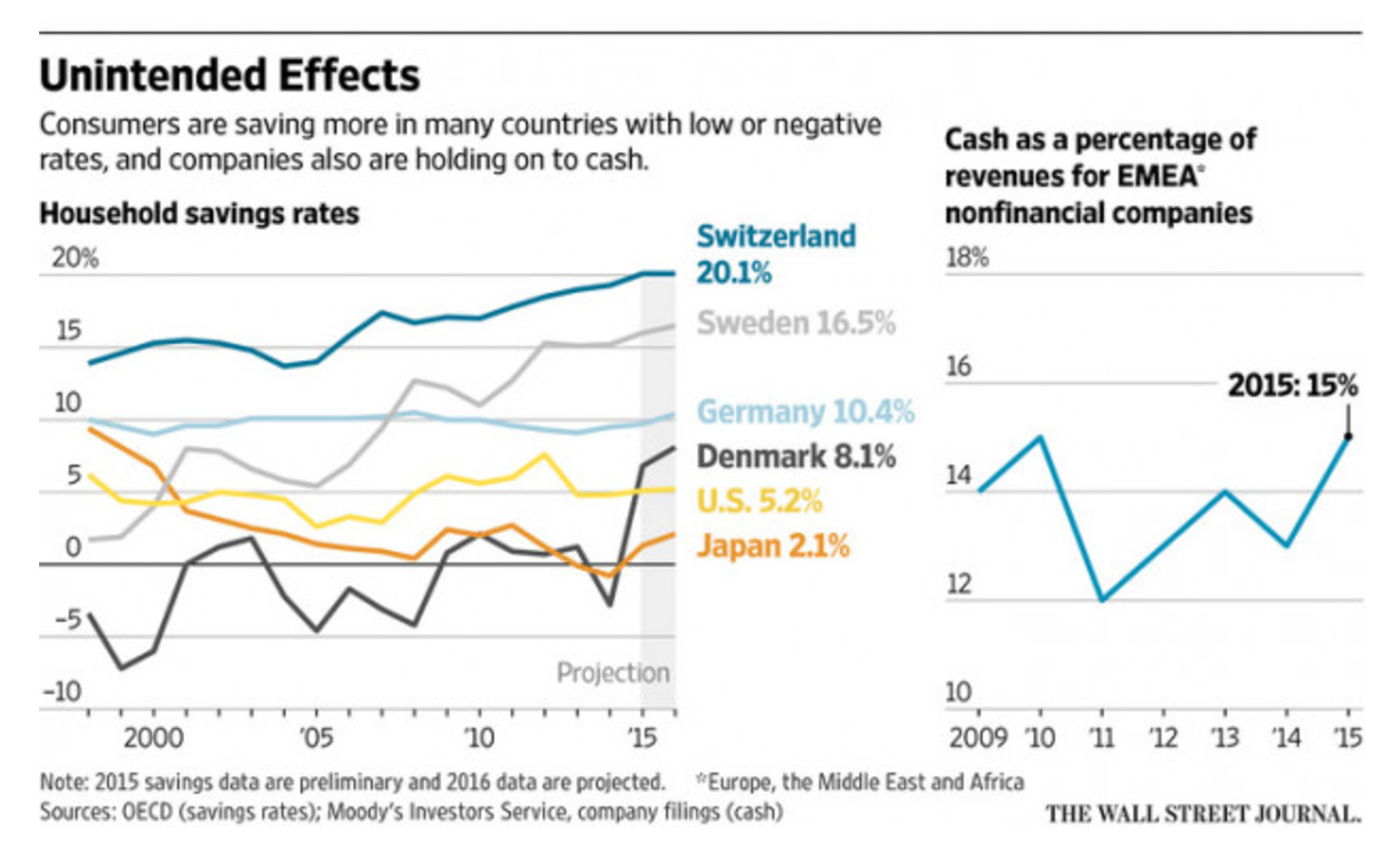

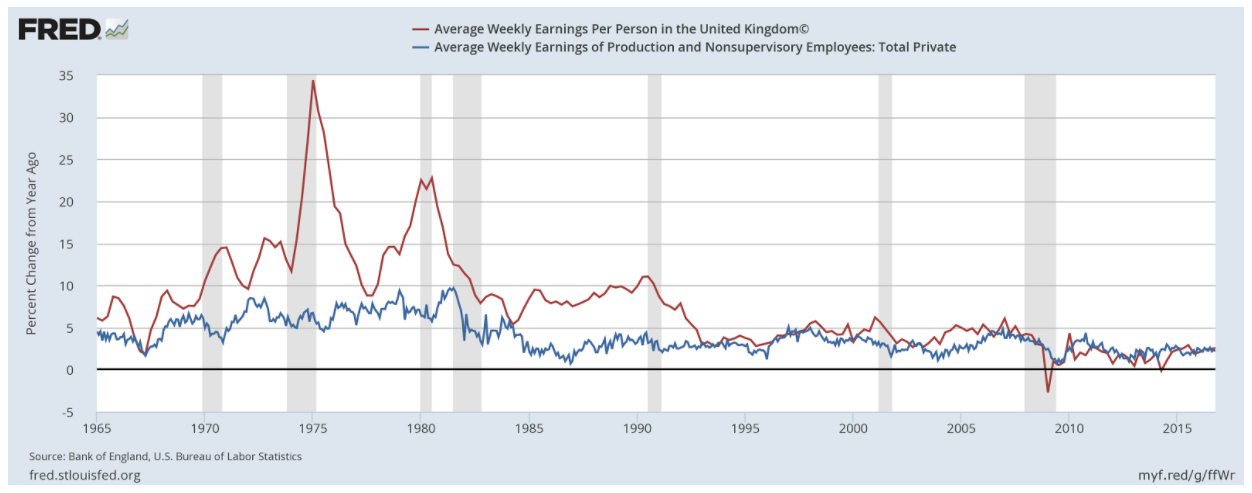

The situation became even worse after the financial crisis erupted. For example, in both the US and the UK the growth of wages slowed even more, as shown in the following figure, even as the headline unemployment returned to pre-crisis levels.

Moving towards a low headline unemployment rate, though, does not mean full employment is being achieved. In the US, the U-6 measure of the unemployment rate, which adds the underemployed to the headline rate, shows that the real unemployment rate is at 8.6%. Far from full employment! In the UK, it has been reported by the Office for National Statistics that the number of people employed in zero-hour contracts has risen by 400% since 2000 but most of the rise happened after the financial crisis. Thus, the employment situation is worse than before the crisis which leads to a further decline in wage growth.

Why is high wage growth important for the recovery?

It is essential to point out that one of the main reasons the current economic recovery has been weak is low wage growth. Wage income is the main propeller of consumer spending, which accounts for more than 60% of GDP in industrialized countries. Low wage growth means low consumer spending, thus low GDP growth and employment. Currently, households are borrowing to keep their living standards stable and that is what’s keeping consumer spending going. This process, though, is unsustainable and will not last long. When households cannot afford to borrow anymore another financial crisis will almost certainly occur. That’s why governments need to do everything in their power to restore wage growth.

What can be done?

The power of organized labor has been decimated since the 1980s. If workers cannot actually have a say in what happens in the workplace then they cannot fight for fair wages. This is why unions need to be strengthened and supported by governments. Employers should be forced to negotiate wages through collective bargaining and union coverage should be expanded above the current 50% OECD average. This will level the playing field between powerful employers and the currently weak labor class.

As mentioned before, productivity and real wages have been delinked since the 1980s. That’s where the minimum wage could potentially help. In the US, the real minimum wage fell after 1980 and has stayed relatively flat since then. With the liberalization “mania” sweeping the western world, governments are freezing public sector pay rises and Greece even cut the minimum wage in the name of restoring public finances and growth. That’s the exact opposite of what should be done to restore growth. Wages drive consumption and growth, cutting them can only depress the economy. Hiking the minimum wage will help sustain consumption based on wages, employment growth and, thus, wage growth.

A sure way to speed up wage growth again is fiscal stimulus. Government spending lifts aggregate demand directly and effectively. If enough spending is injected into the economy, it will create enough jobs to bring full employment. The momentum and labor scarcity created by the stimulus will force wages up and give workers and labor unions more bargaining power. A Job Guarantee Program, if ever implemented, would effectively set a wage floor in the economy, since any person working at a lower wage than the Job Guarantee offers will be given work in the public sector.

The “curse” of low wage growth is not something new and it definitely got exacerbated with the financial crisis. Even though unemployment is currently falling in many countries, it is still way above full employment levels. With workers’ rights under attack for some time now, unions do not have the power they once did to promote strong pay growth. If the current recovery is to accelerate, and for ordinary people to participate in it, wage growth has to rise substantially. The only way to do this is for labor unions to be strengthened and governments to once again commit to full employment.

About the Author

Nikos Bourtzis is from Greece and recently graduated with a Bachelor in Economics from Tilburg University in the Netherlands. He will be pursuing a Master in Economics and Economic analysis at Groningen University. Research interests are heterodox macroeconomics, anti-cyclical policies, income inequality, and financial instability.