The first half of the twentieth century was a challenging time for economics. The Great Depression wiped out incomes, investments, and most importantly, optimism. But when the traditional laissez-faire approach proved ineffective, the work of Keynes and FDR showed that there was another way. The New Deal employed American workers directly and restored confidence among business owners. Today, we could benefit from a similar program. It’s time for a new New Deal, or a Job Guarantee Program, that secures employment to all who are able and willing to work. We’ve done it before, and we can do it again. By Johnny Fulfer.

What We Learned from the Great Depression

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the U.S. economy was in a recession just over 48 percent of the time between 1871 and 1900. But none were as bad as the crisis that followed The Great Crash of 1929. Nevertheless, orthodox economic theorists urged policymakers to maintain the status quo and argued the economy would return to normal as long as it was left alone. This perspective was influential and often framed the ways in which political leaders such as Herbert Hoover understood the crisis. Hoover was not only politically committed to free-market ideas, he was psychologically invested in them, urging Americans to show thrift and self-reliance, practices which later resulted in more turmoil.

Elected president in 1932, Franklin Roosevelt did not have an all-embracing theory that would solve all America’s problems. Rather, he employed a wide range of policies, some of which failed, while others were successful in getting people to work. Perhaps the greatest impact Roosevelt’s New Deal had on American society was the change in perspective policymakers had toward government intervention. Earlier leaders like Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson had had only moderate success producing government initiatives to restrain the predatory nature of American capitalism. But after the Great Depression, FDR helped policymakers and citizens markedly change their views in favor of government assistance, temporarily pushing the conservative opposition to the margins.

As such, FDR’s New Deal momentarily ended the ‘rugged individualism’ of the Hoover era and demonstrated that free-market economics could not be relied upon in a time of crisis. When the economy falls into a slump, the government must be used as a source of relief.

This, too, is the argument that John Maynard Keynes makes in his influential 1936 book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Keynes challenged the neoclassical principle that the market naturally adjusts itself to full employment. Along with the two held theories of unemployment—voluntary and frictional—Keynes wrote, there is also the involuntary, which was the result of a shortfall in aggregate demand.

The volatility of investment, Keynes argued, is dependent on our expectations of the future. The only way entrepreneurs would invest is if they expect sufficient demand for goods and services. This was a problem during the Depression—spending money was scarce. When people are unemployed, or fearful of losing their jobs, they are likely to reduce spending. This creates a cycle of insufficient demand, bringing profit-expectations down. Increasing savings, Keynes showed, would only make things worse. A rise in savings would reduce spending, and thus bring down the total level of employment and income. Surplus inventories with nobody to buy commercial products would force firms to contract operations and lay off even more workers.

Therefore, Keynes concluded, there is no automatic recovery from depression; supply does not create its own demand. The only solution is for the government to heavily invest in public works, creating jobs and increasing demand to rebuild confidence in the business community.

Roosevelt’s New Deal did exactly this. It produced nearly 13 million jobs, over 60 percent of which came from the Works Progress Administration, an organization which hired a wide range of individuals, from artists and writers to laborers who constructed roads, bridges, and schools. An incredible number of public goods were provided through these programs, and money was placed in the hands of the workers, whose purchasing power gave business owners’ profit expectations the much needed boost.

Why We Need a new New Deal

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics recently published a report examining the current employment conditions in the United States. The unemployment rate stands at 4.1 percent, the BLS reports, which is roughly 6.6 million people in the labor force. While the unemployment rate is relatively low from a conventional perspective, Dantas and Wray argue that this does not consider the falling participation rate for prime-age workers and wide-spread income stagnation.

Moreover, we often gauge the economy based on the unemployment rate, although, this economic indicator does not consider the fact that 40.6 million Americans remain in poverty. A job paying the current federal minimum wage doesn’t mean a worker will make enough money to live without relying on various forms of welfare. In order to turn this around, we need a new New Deal.

While the New Deal of the 1930s was a centralized program, controlled by the federal government, Dantas and Wray propose that a “new New Deal” would be more efficient by creating a more decentralized workforce, hired by state and local governments to meet the needs of the local communities, with wages paid by the federal government. They propose a Job Guarantee program.

The idea behind this policy is that those who are involuntarily unemployed don’t have to be if the government supplied them with a job. Economist Carlos Maciel further argues that the Job Guarantee program would cost around 1 percent of the U.S. GDP, providing additional jobs through the multiplier effect. When the government invests $1, it multiplies through consumer spending, turning into $2 or $3 in the real economy. In his General Theory, Keynes estimated the multiplier to be somewhere between 2 ½ and 3.

Employment works in the same manner. If one new job is created from the initial government investment, the consumption created by the additional worker will produce more jobs in other industries, whose consumption will take the process further, until the multiplier is reached. Moreover, this program would redistribute money from current welfare programs toward the Job Guarantee program. Those who are currently under the poverty line will not need traditional welfare benefits if they have jobs that pay a living wage.

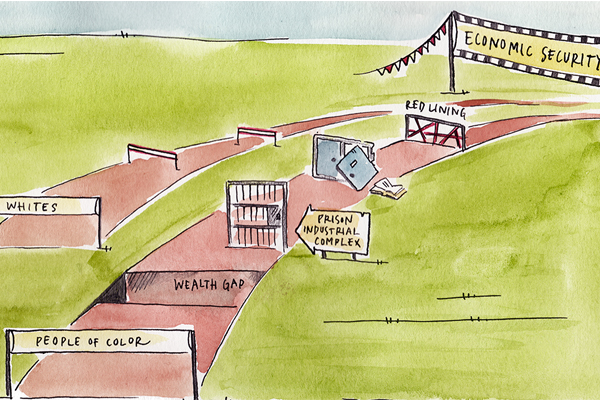

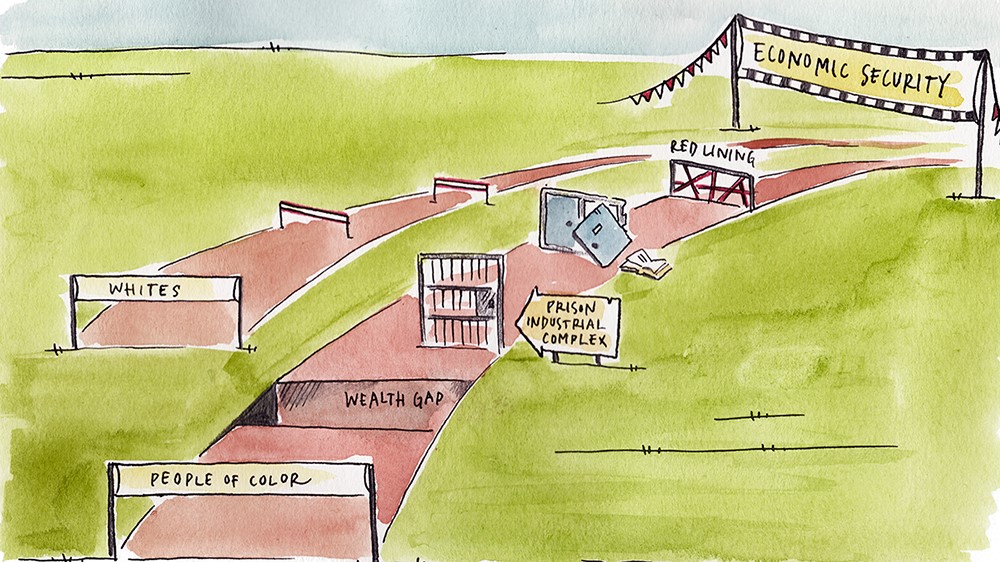

Perhaps the reason U.S. policymakers are hesitant towards a Job Guarantee program has less to do with economics, and more about an investment in the status quo, whether politically or psychologically. Many Americans are invested in the idea of ‘free markets’, whatever they envision that to be, pushing rational economic discourse and the notion of social justice to the margins, and elevating the politically constructed parallel between self-interest and the partial idea of the American Dream. We must move beyond the free-market ideology, which views everything as profit or loss, win or lose. Only time will tell how this polarized form of reasoning will impact the American people, especially the 40.6 million Americans that are currently below the poverty line, who stand to suffer the most.

About the Author: Johnny Fulfer received a B.S. in Economics and a B.S. in History from Eastern Oregon University. He is currently pursuing an M.A. in History at the University of South Florida and has an interest in political economy, the history of economic thought, intellectual and cultural history, and the history of the human sciences and their relation to the power in society.