Derivatives Market as the Achilles’ Heel of the Fed’s Interventions

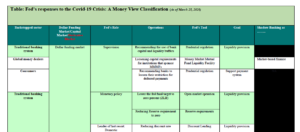

By Elham Saeidinezhad | Some describe the global financial crisis as a “Minsky moment” when the inherent instability of credit was exposed for everyone to see. The COVID-19 turmoil, on the other hand, seems to be a “Mehrling moment” since his Money View provided us a unique framework to evaluate the Fed’s responses in action. Over the past couple of months, a new crisis, known as COVID-19, has grown up to become the most widespread shock after the 2008-09 global financial crisis. COVID-19 crisis has sparked historical reactions by the Fed. In essence, the Fed has become the creditor of the “first” resort in the financial market. These interventions evolved swiftly and encompassed several roles and tools of the Fed (Table 1). Thus, it is crucial to measure their effectiveness in stabilizing the financial market.

In most cases, economists assessed these actions by studying the change in size or composition of the Fed’s balance sheet or the extent and the kind of assets that the Fed is supporting. In a historic move, for instance, the Fed is backstopping commercial papers and municipal bonds directly. However, once we use the model of “Market-Based Credit,” proposed by Perry Mehrling, it becomes clear that these supports exclude an essential player in this system, which is derivative dealers. This exclusion might be the Achilles’ heel of the Fed’s responses to the COVID-19 crisis.

What system of central bank intervention would make sense if the COVID-19 crisis significantly crushed the market-based credit? This piece employs Perry Mehrling’s stylized model of the market-based credit system to think about this question. Table 1 classifies the Fed’s interventions based on the main actors in this model and their function. These players are investment banks, asset managers, money dealers, and derivative dealers. In this financial market, investment banks invest in capital market instruments, such as mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and other asset-backed securities (ABS). To hedge against the risks, they hold derivatives such as Interest Rate Swaps (IRS), Foreign exchange Swaps (FXS), and Credit Default Swaps (CDS). The basic idea of derivatives is to create an instrument that separates the sources of risk from the underlying assets to price (or even sell) them separately. Asset managers, which are the leading investors in this economy, hold these derivatives. Their goal is to achieve their desired risk exposure and return. From the balance sheet perspective, the investment bank is the mirror image of the asset manager in terms of both funding and risk.

This framework highlights the role of intermediaries to focus on liquidity risk. In this model, there are two different yet equally critical financial intermediaries—money dealers, such as money market mutual funds, and the derivative dealers. Money dealers provide dollar funding and set the price of liquidity in the money market. In other words, these dealers transfer the cash from the investors to finance the securities holdings of investment banks. The second intermediary is the derivative dealers. These market makers, in derivatives such as CDS, FXS, and IRS, transfer risk from the investment bank to the asset manager and set the price of risk in the process. They mobilize the risk capacity of asset managers’ capital to bear the risk in assets such as MBS.

After the COVID-19 crisis, the Fed has backstopped all these actors in the market-based credit system, except the derivative dealers (Table 1). The lack of Fed’s support for the derivatives market might be an immature decision. The modern market-based credit system is a collateralized system. To make this system work, there should be a robust mechanism for shifting both assets and the risks. The Fed has employed extensive measures to support the transfer of assets that is essential for the provision of funding liquidity. Financial participants use assets as collaterals to obtain funding liquidity by borrowing from the money dealers. During a financial crisis, however, this mechanism only works if a stable market for risk transfer accompanies it. It is the job of derivative dealers to use their balance sheets to transfer risk and make a market in derivatives. The problem is that fluctuations in the price of assets that derive the value of the derivatives expose them to the price risk.

During a crisis such as COVID-19 turmoil, the heightened price risks lead to the system-wide contraction of the credit. This occurs even if the Fed injects an unprecedented level of liquidity into the system. If the value of assets falls, the investors should make regular payments to the derivative dealers since most derivatives are mark-to-market. They make these payments using their money market deposit account or money market mutual fund (MMMFs). The derivative dealers then use this cash inflow to transfer money to the investment bank that is the ultimate holder of these instruments. In this process, the size of assets and liabilities of the global money dealer (or MMMFs) shrinks, which leads to a system-wide credit contraction.

As a result of the COVID-19 crisis, derivative dealers’ cash outflow is very likely to remain higher than their cash inflow. To manage their cash flow derivative dealers, derive the prices of the “insurance” up, and further reduce the price of capital or assets in the market. This process further worsens the initial problem of falling asset prices despite the Fed’s massive asset purchasing program. The critical point to emphasize here is that the mechanism through which the transfer of the collateral, and the provision of liquidity, happens only works if fluctuations in the value of assets are absorbed by the balance sheets of both money dealers and derivative dealers. Both dealers need continuous access to liquidity to finance their balance sheet operations.

Traditional lender of last resort is one response to these problems. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis, the Fed has indeed backstopped the global money dealer, asset managers and supported continued lending to investment banking. Fed also became the dealer of last resort by supporting the asset prices and preventing the demand for additional collateral by MMMFs. However, the Fed has left derivative dealers and their liquidity needs behind. Importantly, two essential actions are missing from the Fed’s recent market interventions. First, the Fed has not provided any facility that could ease derivative dealers’ funding pressure when financing their liabilities. Second, the Fed has not done enough to prevent derivative dealers from demanding additional collaterals from asset managers and other investors, to protect their positions against the possible future losses.

The critical point is that in the market-based finance where the collateral secures funding, the market value of collateral plays a crucial role in financial stability. This market value has two components: the value of the asset and the price of underlying risks. The Fed has already embraced its dealer of last resort role partially to support the price of diverse assets such as asset-backed securities, commercial papers, and municipal. However, it has not offered any support yet for backstopping the price of derivatives. In other words, while the Fed has provided support for the cash markets, it overlooked the market liquidity in the derivatives market. The point of such intervention is not so much to eliminate the risk from the market. Instead, the goal is to prevent a liquidity spiral from destabilizing the price of assets and so, consequently, undermining their use as collateral in the market-based credit.

To sum up, shadow banking has three crucial foundations: market-based credit, global banking, and modern finance. The stability of these pillars depends on the price of collateral, price of Eurodollar, and price of derivatives, respectively. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis, the Fed has backstopped the first two dimensions through tools such as the Primary Dealer Credit Facility, Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility, and Central Bank Swap Lines. However, it has left the last foundation, which is the market for derivatives, unattended. According to Money View, this can be the Achilles’ heel of the Fed’s responses to the COVID-19 crisis.

Elham Saeidinezhad is lecturer in Economics at UCLA. Before joining the Economics Department at UCLA, she was a research economist in International Finance and Macroeconomics research group at Milken Institute, Santa Monica, where she investigated the post-crisis structural changes in the capital market as a result of macroprudential regulations. Before that, she was a postdoctoral fellow at INET, working closely with Prof. Perry Mehrling and studying his “Money View”. Elham obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Sheffield, UK, in empirical Macroeconomics in 2013. You may contact Elham via the Young Scholars Directory