After the 2009 recession, Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman wrote a New York Times article entitled “How did economists get it so wrong?” wondering why economics has such a blind spot for failure and crisis. Krugman correctly pointed out that “the economics profession went astray because economists, as a group, mistook beauty, clad in impressive-looking mathematics, for truth.” However, by lumping the whole economics profession into one group, Krugman perpetuates the fallacy that economics is one uniform bloc and that some economists whose work is largely ignored had indeed predicted the financial crisis. These economists were largely dismissed for not falling into what Krugman calls the “economics profession.”

So let’s acknowledge there are many types of economics, and seek to understand and apply them, before there’s another crisis.

Left economics understands power

Let’s take labor as an example. Many leftist economic thinkers view production as a social relation. The ability to gain employment is an outcome of societal structures like racism and sexism, and the distribution of earnings from production is inherently a question of power, not merely the product of a benign and objective “market” process. Labor markets are deeply intertwined with broader institutions (like the prison system), social norms (such as the gendered distribution of domestic care) and other systems (such as racist ideology) that affect employment and compensation. There is increasing evidence that the left’s view of labor is closer to reality, with research showing that many labor markets have monopsonistic qualities, which in simple terms means employees have difficulty leaving their jobs due to geography, non-compete agreements and other factors.

In contrast, mainstream economics positions labor as an input in the production process, which can be quantified and optimized, eg. maximized for productivity or minimized for cost. Wages, in widely taught models, are equal to the value of a worker’s labor. These unrealistic assumptions don’t reflect what we actually observe in the world, and this theoretical schism has important political and policy implications. For some, a job and a good wage are rights, for others, businesses should do what’s best for profits and investors. Combative policy debates like the need for stronger unions vs. anti-union right-to-work laws are rooted in this divide.

The role of government

The left believes the government has a role to play in the economy beyond simply correcting “market failures.” Prominent leftist economists like Stephanie Kelton and Mariana Mazzucato, argue for a government role in economic equity and shared prosperity through policies like guaranteed public employment and investment in innovation. The government shouldn’t merely mitigate product market failures but should use its power to end poverty.

On the other hand, mainstream economics teaches that government crowds out private investment (research shows this isn’t true), raising the wage would reduce employment (wrong) and that putting money in the hands of capital leads to more economic growth (also no). As we have seen post-Trump-cuts, tax cuts lead to the further enrichment of the already deeply unequal, equilibrium.

Limitations to left economics: public awareness and lack of resources

History and historically entrenched power determine both final outcomes but also the range of outcomes that are deemed acceptable. Structural inequalities have been ushered in by policies ranging from predatory international development (“free trade”) to domestic financial deregulation, meanwhile poverty caused by these policies is blamed on the poor.

Policy is masked by theory or beliefs (eg. about free trade), but the theory seems to be created to support opportunistic outcomes for those who hold power to decide them. The purely rational agent-based theories that undergird deregulation have been strongly advocated for by particular (mostly conservative) groups such as the Koch Network which have spent loads of money to have specific theoretical foundations taught in schools, preached in churches and legitimized by think tanks.

There have been others who question the centrality of the rational agent, the holy grail of the free market, believe in public rather than corporate welfare, and the need for government to not only regulate but to make markets and provide opportunity. This “alternative” history exists but is less present – it’s alternative-ness defined by sheer public awareness, lack of which, perhaps, stems from a lack of capital.

Financial capital is an important factor in what becomes mainstream. I went through a whole undergraduate economics program at a top university without hearing the words “union” or “redistribution,” which now feels ludicrous. Then I went to The New School for Social Research for graduate school, which has been called the University in Exile, for exiled scholars of critical theory and classical economics. In the New School economics department, we study Marxist economics, Keynesian and post-Keynesian economics, Bayesian statistics, ecological and feminist economics, among others topics. There are only a few other economics programs in the US that teach that there are different schools of thought in economics. But after finishing at the New School and thinking about doing a PhD there, I understood this problem on a personal level.

There’s barely any funding for PhDs and most have to pay their tuition, which is pretty unheard of for an economics doctorate. Why? Two reasons – 1. Because while those who treat economics like science go on to be bankers and consultants, those who study economics as a social science might not make the kind of money to fund an endowment. And 2. Perhaps because of this lack of future payout, The New School is just one of many institutions that doesn’t deem heterodox economics valuable enough to warrant the funding that goes to other programs, in this case, like Parsons.

Unfortunately, a combination of these factors leaves mainstream economics schools well funded by opportunistic benefactors, whether they’re alumni or a lobbying group, while heterodox programs struggle or fail to support their students and their research.

The horizon for economics of the left

Using elements of different schools of thought, and defining the left of the economics world, is difficult. Race, class, and power, elements that define the left, are sticky, ugly, and stressful, and don’t provide easily quantifiable building blocks like mainstream economics does. Without unifying building blocks, we’re prone to continuing to produce graduates from fancy schools who go into the world believing that economics is a hard science and that the world can be understood with existing models in which human behavior can be easily predicted.

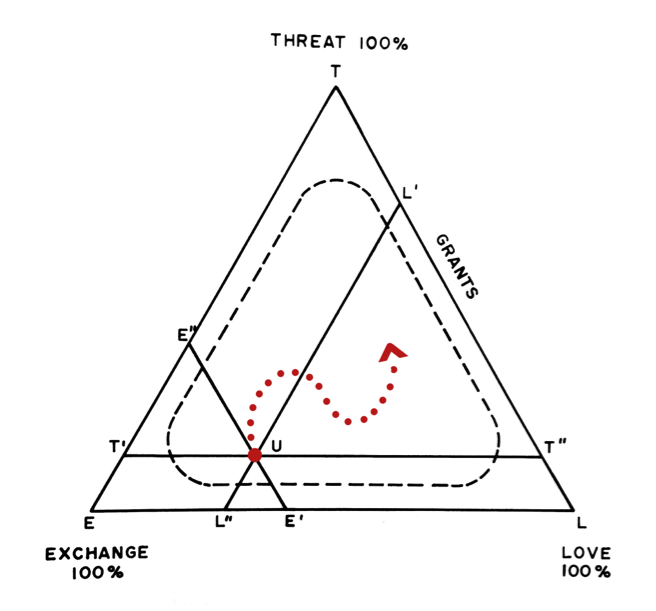

Ultimately the mainstream and the left in economics are not so different from the mainstream and the left politically, and there is room for a stronger consensus on non-mainstream economics that would bolster the left politically. It’s worth exploring and strengthening these connections because at the heart of our economic and political divides is a fundamental difference in opinion regarding how society at large should be organized. And whether we continue to promote wealth creation within a capitalistic system, or a distributive system that holds justice as a pinnacle, will determine the extent to which we can achieve a healthy, civilized society.

Fortunately, the political left in many ways is upholding, if not the theory and empirics, the traditions and values of non-mainstream economics. Calls from the left to confront a half-century of neoliberal economic policy are more sustained and perhaps successful than other times in recent history, with some policies like the federal job guarantee making it to the mainstream. After 2008 the 99 percent, supported by mainstreamed research about inequality, began to organize.

There’s hope for change stemming from a new generation of economists, in particular, the thousands of young and aspiring economists researching and writing for groups like Rethinking Economics, the Young Scholars Initiative (YSI), Developing Economics, the Minskys (now Economic Questions), the Modern Money Network, and more. But ideas and policies are path dependent, and it will take a real progressive movement, supplemented by demands by students in schools, to bring left economics to the forefront.

By Amanda Novello.

A version of this post originally appeared on Data for Progress’ Econo-missed Q+A column, in response to a question about the marginalization of leftist voices in economics.

Amanda Novello (@NovelloAmanda) is a policy associate with the Bernard L. Schwartz Rediscovering Government Initiative at The Century Foundation. She was previously a researcher and Assistant Director at the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis at The New School for Social Research.