You work all the time. But what is work, really? And how has that changed? In Work: A Deep History, from the Stone Age to the Age of Robots, anthropologist James Suzman digs into these questions. But whether he realizes it or not, he leaves an even bigger one to us.

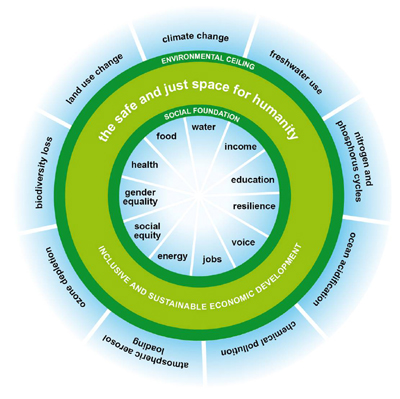

The future of work is a hot topic. Automation, climate, and inequality make us wonder what’s coming down the pipe, and how to prepare. We might have to change how work works by decoupling labor from pay… difficult questions. But one thing is clear: if we are to change our conception of work, it will help to understand the one we have.

So what’s work, really?

Suzman starts at the beginning—3.5 Billion years ago. Because at its essence, he argues, work is not whatever you get paid for. It is a transfer of energy.

Thanks to the law of entropy, he explains, everything in the universe tends to chaos. Life forms impose some kind of order, but creating and maintaining that order takes energy. It requires work to grow leaves or make honey or build a house. So yes, even bacteria and trees do work, despite the fact that they don’t have thoughts about it.

So, Suzman posits that the act of work has been around for a long time, but the idea of work is newer. He explains that our mastery over fire was a likely catalyst. In reducing the energy required to survive, fire gave us leisure. And that might have helped us conceive of its counterpart: work.

How has it changed?

With that energy-definition in place, Suzman talks us through work’s cultural evolution. We start with hunter gatherers: there’s a Kalahari desert tribe who still hunt large animals by chasing them down on foot, just like back in the day. They run until the animal is so dehydrated that it lays down and awaits their spear.

He points out that although such hunts are exhausting, the tribe is lounging most of the time. They conceive of the world as abundant, and have no concept of private property. You only worry about your immediate needs, which are almost always met.

With the arrival of agriculture, that’s what we lost. Because Suzman suspects that the first food surpluses also introduced the concept of scarcity. Once you have a pile of crops, that pile—unlike nature—starts and ends somewhere. And it can be said to belong to somebody.

So farming ushered in modern economics. We started thinking everything was scarce, and inequalities increased. At the same time, farmers had to wait for their crop to mature and thus needed to live on credit for much of the year. So by keeping a record of their debt we created—you guessed it—money.

After that it’s domesticated animals, machines, cities, and the industrial revolution, causing living standards to rise. Working hours rose, then fell, then rose again. Suzman takes us past Luddites, the Great Depression, JK Galbraith, and the War on Talent, all the way until the present where we continue to work a lot while AI seems to breathe down our neck.

As he sends us off, Suzman admits that we can’t go back to hunter-gathering, but hopes that we take inspiration from the tribes and broaden our understanding of work. He reminds us that scarcity and limitless needs are not inevitable truths, nor are they necessary assumptions. These are fantastic points and his detailed evolution of work is very insightful. But it’s missing a piece.

Now for the biggest question

Imagine that you decide to clean up your room, and you call Suzman in to help. He comes over and finds all kinds of junk drawers you didn’t even realize you had, and he spreads the contents all over your living room floor. Then he leaves.

He helped with a crucial step. To reorganize something, you need to know what you’ve got, and identify all the items. But to put them in a better place, you need to know what they’re for. Why did you buy the things you own? And what’s your purpose in rearranging?

To put it bluntly, Work falls short on the question of why. It’s a big book about what we’ve been doing, without much to say about what we do it for.

To be fair, there are occasions where motives are discussed. One is when he points to a rare bird that builds very elaborate nests only to break them apart and all start over again. Similarly, some people run ultramarathons. Darwin’s survival of the fittest can’t explain it, Suzman says, so it’s probably a way to get rid of energy surpluses.

I can’t explain the bird either. But ask any ultramarathon-runner, and I bet they’ll tell you they did it because it was a meaningful experience—not because they were sitting on the couch bouncing up and down and only 31 miles would do the trick.

The second occasion is consumer culture. Suzman cites Galbraith who points to the way advertisers exploit our relative needs, making us want to work more to buy more. This undoubtedly plays a role. And to state the obvious, many of those less affluent will do any work that can help them survive.

But is that it?

Consider your own case

Why do you do the job you have? Is it the easiest way to survive? Is it a means to get rid of surplus energy? I doubt it. The right kind of work GIVES you energy. How does it do that? Because it’s meaningful. Why is it meaningful? Because you are able to contribute something. You are able to make a change. You are fulfilling a purpose you set for yourself. So these are the questions to ask: What’s the work out there that we think needs doing? What should work be for?

Perhaps Suzman didn’t get to these questions because there wasn’t much room for them in the past. In that case, fair enough. It may be that today’s circumstances of relative affluence and increasing levels of automation give them real relevance only now. But if we want a concept of work that we can carry forward, we can’t let ‘em drop.

And Suzman will be happy to know that there are plenty of young economists ready to do away with the assumptions of scarcity and limitless needs. But doing away with things is not enough. We need to introduce some new stuff too. And if you’re asking me, that new stuff is meaning.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got some work to do •

About the Author: Heske van Doornen is Manager of the Young Scholars Initiative and co-founder of this blog. Twitter: @HeskevanDoornen

Buy the Book

Work: A Deep History, from the Stone Age to the Age of Robots Book

By James Suzman | Penguin Press (2021)

Want to review a book you read? YSI will reimburse you for the price of the book, and will consider your piece for publication on Economic Questions. Reach out to contact@economicquestions.org to get started.