“Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favorable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.” This is Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declared by the UN in 1948. It sounds like a pretty good right to me. I recently learned that in America, we have some states with “right-to-work” laws. That dumbfounded me. Why did unemployment exist in those states if they had a right to work?

It only took a few minutes of research to find out that the “right-to-work” laws some states have are nothing like the fundamental human right. What these laws actually do is defend a worker’s right not to be required to join a labor union to work at a company. This “right-to-work” doesn’t allow more choice, it allows less. Where’s the option to have a union that doesn’t allow freeriders? If you don’t want union benefits, you can work for a company without a union. You still have your choice, but this law has destroyed mine. These laws really promote the right to work for less money, the right to work at a business with a racist union, the right to destroy what unions could and should stand for.

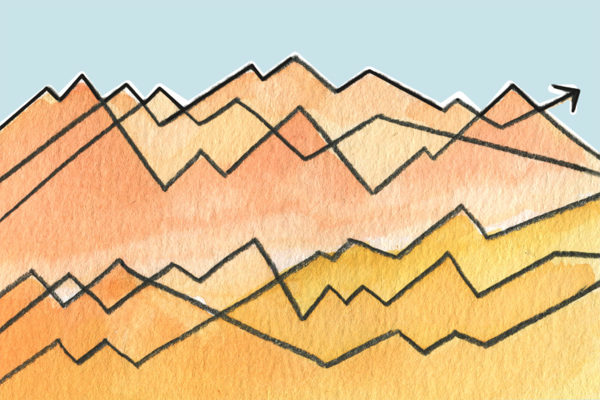

Research from the Economic Policy Institute shows that states with “right-to-work” laws have hurt unionization rates, and hurt the power of unions that do exist. In such states 7% of workers are represented by a union contract, versus 17% in non “right-to-work” states. Wages are lower in states with these laws in place, which makes sense as unions allow collective bargaining for better wages. Nationally, unionized workers are making 27% more than non-unionized workers. “Right-to-work” has been a disaster for the labor movement, those who historically have won us better pay for shorter hours and better working conditions. Those who won us the weekend. Those who won women the right to vote. Those who won us the 8 hour work day.

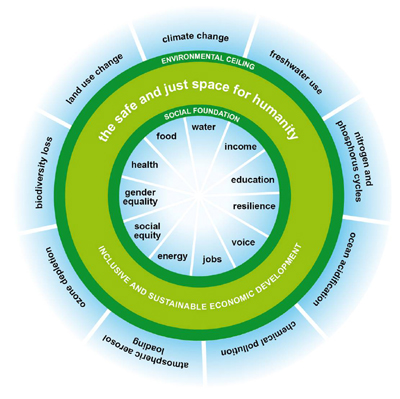

To reinvent the labor movement we have a lot of ground to cover. One way to start would be with reimagining the “right-to-work” to be much more like the fundamental human right envisioned by the UN in 1948. This actual Right to Work, a Job Guarantee, would transform the labor market. It’d be up to communities to decide what jobs to guarantee as they see fit, but surely our communities could come up with something better than a new fast food joint. If you’re guaranteed a job serving your community, wages will go up across the board, as entry-level workers get real choice. Capitalists would be forced to make burger flipping more attractive than planting trees.

The real human right to work would mean you could quit working for your abusive boss and cross the street and get hired. We could make job guarantee jobs come with awesome benefit plans, that capitalists are forced to match. We could have contracts with our employers that require “just cause” to be fired, rather than the uneven “at-will” employment contracts we all toil under today. We could have unions that represent all of the workers in our businesses rather than just a small subset. It’s going to take a lot of work to get there, but coalescing around a shared demand, a good job for everyone, is a great start.

We can see the work that needs to be done. We need care workers to serve our aging population. We need police officers that actually serve our communities. We need solar panels harnessing the free energy of the sun. We need to capture the carbon capitalists have polluted the environment with. We need affordable housing so we don’t have people living on the streets. We need the right to build these things together, including everyone willing and able. We need to take care of those who aren’t able, for whatever reason. If we reimagine a true right to work, the unimaginable becomes possible.

believed to be a distinct system with its own logic that requires experts to manage it.” Their work carefully explains why our current system is an econocracy and discusses possible ways to change that. Based on my own experiences so far, I can’t help but agree with them.

believed to be a distinct system with its own logic that requires experts to manage it.” Their work carefully explains why our current system is an econocracy and discusses possible ways to change that. Based on my own experiences so far, I can’t help but agree with them.